A Failure of Timing or a Failure of Foreign Policy? Lessons Learned from Canada’s Failed UNSC Bid

Image credit: “United Nations Security Council” by Neptuul

The perception surrounding Canada’s failure to secure a seat on the UNSC has been widely regarded as a pivotal moment for the nation’s foreign policy. However, the defeat does not equate to the decline of Canada’s international image; rather, it is a chance to refocus domestic policy and international efforts where they are most needed.

By Sarah Sutherland | Canada’s Role on the Global Stage Policy Researcher

Canada’s bid for a seat on the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) came to a close on 17 June, 2020, when the country failed to secure the necessary 2/3 votes. Competing against Ireland and Norway, Canada faced tough opposition – both abroad and here at home – from national experts, the general public, and allied states. This issue brief aims to highlight various critiques of the Trudeau administration’s timing, policy, and campaign for the UNSC seat, and poses various recommendations for Canada’s future.

On 17 June 2020, Canada competed against Ireland and Norway for the Western European and Other Group’s (WEOG) seats on the United Nations Security Council (UNSC). Allocated two council seats that rotate on a biennial basis, this is not the first time Canada has failed to gain one of the seats available for the WEOG group. Under the Harper administration, Canada was skipped over in favour of Portugal and Germany in 2010. In the most recent UNSC elections, and despite the Trudeau administration’s final push, Ireland and Norway were able to secure the necessary 2/3 of the vote to win, with the nations garnering 128 and 130 votes respectively. Canada’s second failed bid in the past decade, which saw the nation obtain only 108 votes compared to the 114 received under Prime Minister Harper, has raised questions about messaging and the clarity of Canada’s foreign policy. There appears to be a gap between how Canada perceives itself and how other nations view its contributions to the international community

Although Canada spent more than $2 million on their UNSC campaign, the effort was thwarted by an unclear message. With a wide gap between rhetoric and action, for many it was not a surprise that Canada failed to achieve its goal. Leading up to the 17 June vote, it was noted that Prime Minister Trudeau and his team mounted a final push to secure votes which involved calling leaders in nations such as India, Pakistan, North Macedonia, and Fiji. Similarly, it was only in February 2020 that the Prime Minister and members of his team flew to Senegal, Ethiopia, and Germany to pitch Canada’s candidacy for the seat – a far cry from the staggering years-long campaign mounted by Ireland and Norway. Many have critiqued this style of pitching, including Mark Kersten, Deputy Director of the Wayamo Foundation.

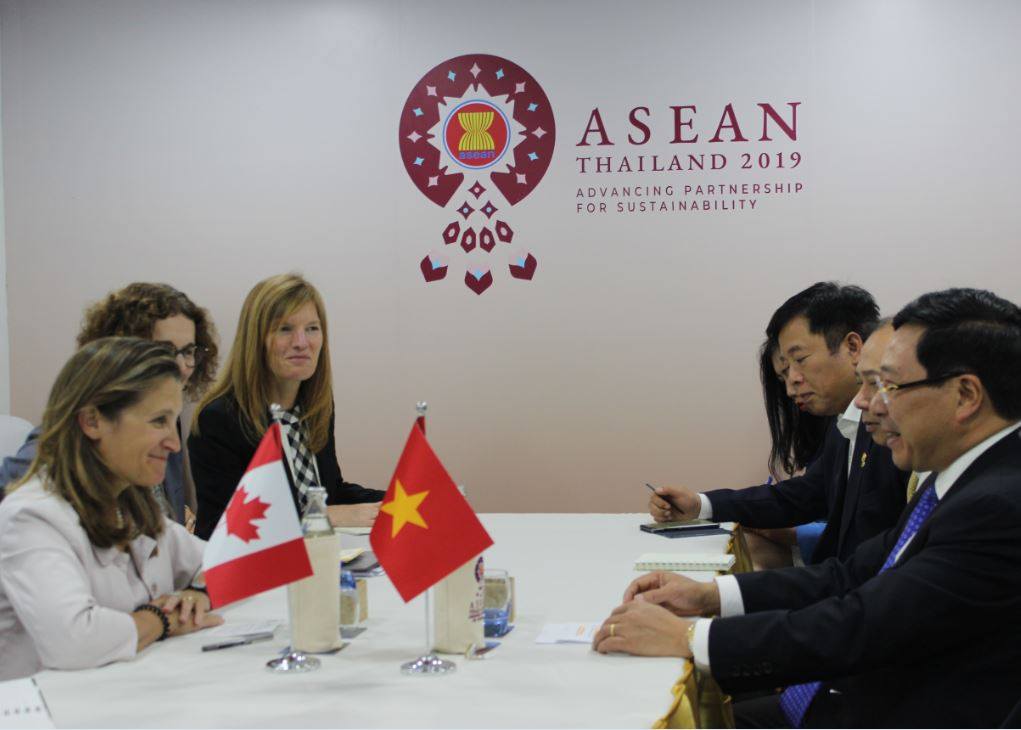

Press Conference by Prime Minister of Canada by United Nations Photo

“If [Prime Minister Trudeau] had five years, why would [he] wait so long for these trips and meetings?” Kersten questioned during an interview with The Guardian. He further noted that building the goodwill and relations with other states that is necessary to get the votes for a UNSC seat does not happen overnight. It is therefore no surprise to him that Prime Minister Trudeau’s last-minute efforts did not equate to adequate votes for the nation.

Many, including Kersten, have criticized the seeming hypocrisy of Canada’s current feminist foreign policy in recent years as well. Kersten highlighted that to have such a policy, Canada needs to ensure every “decision that’s relevant to Canadian international relations should be examined through its gender dimensions,” which is not the current case with Canada’s deal with Saudi Arabia or relations with China. Some have even highlighted the Prime Minister’s previous defence of SNC-Lavalin, which had admitted fraud and bribery in countries like Libya, as a key instance in which Canadian policy and action did not line up. As the UN is one of the largest international forums, the importance of a voice in discussions within the UN system is critical; but a nation needs a clear foreign policy to do so.

The significance of the UNSC and its rotating seats was underscored by Bessma Momani, a Senior Fellow at the Centre for International Governance and Innovation and a Professor of Political Science at the University of Waterloo, in a discussion with CBC News. She maintained that the loss of a seat at arguably the most powerful international table should act as a wake-up call for Canadians. This is due to the fact that although there are problems within the UN, there is still merit in being involved in the system because “organizations are only as good as the people who get engaged in them.”

Similarly, Thomas Juneau, Professor of International Affairs at the University of Ottawa, suggested that although Canada appears to support many initiatives rhetorically, Canada’s current commitment to initiatives like Peacekeeping, a historical cornerstone of Canada’s international legacy, is at a 60-year low. Canada’s recent mission to Mali, the largest in nearly a generation and only lasted one year, “reinforced the perception that [Canada] wanted to tick a box as opposed to really doing the heavy lifting.” Juneau, like his colleagues, hope that the unsuccessful UNSC bid will prompt a re-examination of Canada’s foreign policy and the goals it hopes to achieve.

In comparison, Robert Fowler, Canada’s longest-serving ambassador to the United Nations, has suggested that Prime Minister Trudeau’s refusal to denounce American President Trump on various issues is also a compounding factor. Referring to Prime Minister Trudeau’s awkward 21-second pause following a question regarding President Trump’s suggestion of sending in the military to stop protests in the United States following George Floyd’s murder, Fowler noted that this was not a good sign for allies. Fowler suggested that the pause indicated to nations that “if you elect Canada, you’re electing a second Trump” within the Security Council, which is already marred by a deadlock between the feuding Permanent 5 members. With high tensions between states like the United States and China, such a comparison did little to help Canada’s campaign.

“Foreign Leader Visits” by The White House

Other experts suggest that Canada should not have attempted the UNSC bid in the first place. Janice Stein, Professor at the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy, has vocally opposed the bid since it was originally suggested in 2016. Stein noted that given the current tension between Permanent 5 members, largely the United States and China, Canada would have put itself directly in the ‘firing line’ of power politics. In a panel discussion with CBC News, Stein said that obtaining the UNSC seat would have forced Canada to take a concrete position when the national strategy has typically been to “choose the areas where [it] wants to weigh in.” Although her opinion is largely indicative of failure of Canadian foreign policy, she notes that the opposite is true.

Stein does not believe that Canada’s international image should solely be based on the UNSC loss, and states that the UNSC just may not be the forum in which Canada is best posed to engage in. She has gone on to highlight the important work Canada has achieved regarding the reform of the World Trade Organization and generally shifting the UN towards sustainable development; all of which has taken place in other key forums.

Following the defeat, Foreign Affairs Minister François-Philippe Champagne attempted to soften the UNSC loss by stating that the campaign itself was the goal, as it allowed Canada to become more present around the globe. However, many outside the Liberal caucus did not take such a view. Prior to the vote, Conservatives had already suggested that even if Canada did receive the required votes it would have been because the “Liberal government had been less principled in its pursuit;” the government had conceded too much to obtain the seat. In 2019, Andrew Scheer, the previous Conservative Party leader, told the Globe and Mail that although Canada can play an immensely valuable role on the international stage, that role should not come at the “expense of selling out our principles or selling out our long-standing positions on various issues.”

Scheer was quick to criticize the outcome of the bid on 17 June as “another foreign affairs failure for Justin Trudeau,” doubling down on the previous comments made by the Conservative Party. Other parties have also been critical of Prime Minister Trudeau’s decision to run for the UNSC seat, given the late stage of competition.

The New Democratic Party (NDP) released a statement following the defeat noted the shortcomings of Canadian foreign policy in the recent decade that contributed to the failed bid. The NDP noted that under the current Liberal government, “Canada’s Official Development Assistance is just a third of what it should be – smaller than the contribution of the Harper years…[and] the Canadian government has been inconsistent in [its] support for human rights.” Going forward from the UNSC vote, the NDP Critic for Foreign Affairs Jack Harris highlighted that Canada needs to repair the damage to our reputation and focus on keeping the commitments we make to the international community.

The Bloc Québécois also echoes the feeling that the loss of the UNSC seat is related to the failure of Canada’s foreign policy in recent years. Yves-François Blanchet, leader of the Bloc Québécois, spoke with CTV News a day after the UNSC loss and stated that the defeat was simply part of a “larger trend in a foreign policy that has failed to get results.” Pointing to tension with China, the continued arms sales to Saudi Arabia, and the failure to obtain the flight records from the downing by Iran of an airliner with Canadians on board, Blanchet underscored that recent events and global decisions have “stained Canada’s international prestige.”

In order to restore it, it has been argued by various parties that Canada needs to take this time to rethink its global priorities – a sentiment that is mirrored by surveys conducted recently by groups such as EKOS Research Associates. Their survey was designed to ask Canadians about issues relating to areas where Canada appears to fall behind on key issues compared to its UNSC competitors, including climate change, peacekeeping, and developmental assistance.

“50th Anniversary of Canada’s Peacekeeping Mission to Cyprus | 50e anniversaire de la mission de maintien de la paix à Chypre” by VAC-ACC

Taking place between 5 June and 10 June 2020 on behalf of the Canadians for Justice and Peace in the Middle East, Independent Jewish Voices Canada, and the United Network for Justice and Peace in Palestine-Israel, the EKOS survey confirmed what most academics and political parties have suspected – that the current Canadian foreign policy is “out of touch with the preferences of Canadians.” However, the topics that they believe the policy is out of touch with depends on which political party they are affiliated with. There is a noticeable polarization between supporters of the Conservative party and all other parties’ supporters.

For example, the survey found that at large, most Canadians are supportive of increasing the nation’s contributions to the global community. This includes a large majority supporting an increase of funding to climate change initiatives, with Liberal (77%), NDP (98%), and Green (90%) voters leading the support. Conservative supporters felt drastically different, with only 18% noting their support for increasing funding for climate change initiatives. In general, the EKOS survey highlights the divergence between political views regarding Canada’s contribution on the world stage; a divide many Canadians already knew about. Similarly, the survey highlighted that despite the federal cuts to Canada’s commitments and funding to global initiatives, Canadians themselves are “generally supportive of increasing Canada’s contributions to the international community” as a whole.

The Canadian loss of a UNSC seat has also raised concern for like-minded nations, and fellow WEOG states, such as Australia and New Zealand. With continued attacks on multilateralism by the American President and the failure of a typically strong middle power such as Canada to obtain a seat, like-minded states are becoming increasingly concerned about what this will mean in the future. This unease also stems from the fact that many Latin American and African states have shifted toward Chinese revenue flows and loans, which can have a strong influence on their voting patterns. It has been suggested that countries like Australia and Canada should “structure a like-minded international political alliance” with other democratic states, such as Japan, South Korea, Vietnam, and India to act as a counterweight to Chinese power in the global arena. This would extend to voting in UNSC elections as well; however, this alliance could only work if nations like Canada gave more warning when attempting to secure a seat.

Traditionally, countries like New Zealand have given their full support to Canada and even gone so far as withholding its second vote (or what is known as voting short) so that Canadian opposition has a difficult time reaching the needed 2/3 voting threshold. However, despite the Canada-Australia-New Zealand voting sub-group, by the time Canada announced its bid for the contested UNSC seat this time around, New Zealand had already promised one of its two votes to Ireland years prior. Without that single vote, Ireland would not have been able to reach the 2/3 voting threshold and voting would have been pushed to a second round.

For Adam Chapnick, a Professor of Defence Studies at the Royal Military College of Canada, Canada’s defeat reflects a “failure of political judgement [and timing] more than it does a failure of foreign policy.”

In short, Canada simply chose the wrong time to run. Regardless of timing, rising global tensions between nations, or the political division becoming apparent within Canada, we must now focus on Canada’s global future.

Experts have suggested various ways in which Canada could re-examine its foreign policy and priorities moving forward. Allan Rock and Sergio Marchi have created such a set of recommendations for the Canadian government. First, they suggest that Canada needs to generally re-evaluate its global priorities and examine best practices regarding promotion. They believe that an all-party parliamentary committee should be created for this specific purpose so that opinions from all sides of the political spectrum are considered. Further, Rock and Marchi highlight the constant defunding of Global Affairs Canada (formerly the Department of Foreign Affairs) as a central issue. If Canada hopes to best promote its interests and support global initiatives, it needs to ensure it has the funding to do so. Thirdly, they suggest that Canada should broaden its efforts to strengthen global governance.

Outside of the UN, Canada is a member of various international groups including the G7, G20, La Francophonie, and NATO. Rock and Marchi therefore note that Canada could leverage their other networks and memberships to foster better global cooperation and promote Canadian leadership. Finally, they suggest that Canada should continue to follow through on its campaign commitments, including focusing greater international attention on the development of the Global South. Rock and Marchi note that this recommendation could be achieved through asking the parliamentary committee to tell the public whether Canada is contributing enough to foreign aid in respect to the size of our economy.

“NATOs hovedkvarter” by Utenriksdept

While some experts have focused their efforts on suggesting recommendations for the Canadian government, others have taken a more ground level approach. Ben Rowswell and the Canadian International Council (CIC) are joining Global Canada and other partners to create Open Canada and explore what a new Canadian foreign policy could look like through citizen engagement. Initially, Rowswell, President and Research Director of the CIC and former Canadian Ambassador to Venezuela, was surprised at the “breadth of opposition to Canada’s pursuit of a seat on the [UNSC]” prior to the voting in June. In part, this was due to the fact that in a rules-based international order, the UN is the global body in which the rules are enshrined, so countries should strive to engage in it. However, he acknowledged in a CBC Radio interview following the defeat that the COVID-19 pandemic has “forced us to confront the reality that the rules-based international order is now over.” Therefore, Canada has essentially run into a dead-end in regards to its foreign policy as a result.

Speaking alongside Fowler, Rowswell highlighted that the loss of the UNSC seat and the current COVID-19 pandemic has given Canada a chance to pursue a foreign policy that takes full account of the power to secure international cooperation going forward.Therefore, Rowswell and the CIC’s creation of the Open Canada platform will act as a connection between citizens and foreign policy in order to highlight the areas of most concern. Open Canada is centred upon the perspective of citizens and suggests that Canada may need to rethink national security. Specifically, the COVID-19 pandemic has illustrated that nations with high levels of social trust and policies based on science have had higher success in containing the spread of the virus. Therefore, national security can no longer be thought of in a physical or cyber realm; other sectors need to be placed on higher priority as well. Open Canada will therefore act as a central point of discussion for these key topics and allow citizens to directly engage in conversations previously only few were able to join.

In short, perception surrounding Canada’s failure to secure a seat on the UNSC has been widely regarded as a pivotal moment for the nation’s foreign policy. Although some experts viewed the initial decision to run as a poor choice, and the campaign itself as lack-luster, the following consensus is that this defeat does not equate to the decline of Canada’s international image; rather, it is a chance to refocus domestic policy and international efforts where they are most needed.

Sarah is a recent Master of Global Affairs graduate from the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy with an emphasis in Justice and Security Studies. She has also obtained a Hon. BA in International Relations, an Honours in Global and Intercultural Engagement, and a Minor in English from Western University. Following an academic exchange at the University of St Andrews in Fife, Scotland, she was inspired to pursue research on the impact of the United Nations’ peacekeeping and humanitarian missions, specifically in Central Europe and the former Belgian colonies in Africa. She has therefore focused her research on the role of gender and ethnicity in various security contexts and has recently pursued research on the security concerns surrounding the commercialization of outer space. From her time interning at the Permanent Mission of Canada to the United Nations in Geneva, Switzerland, she has further developed her passion for promoting gender inclusiveness in security resolutions in order to foster stronger multinational engagement on key disarmament and human rights resolutions.

The perception surrounding Canada’s failure to secure a seat on the UNSC has been widely regarded as a pivotal moment for the nation’s foreign policy. However, the defeat does not equate to