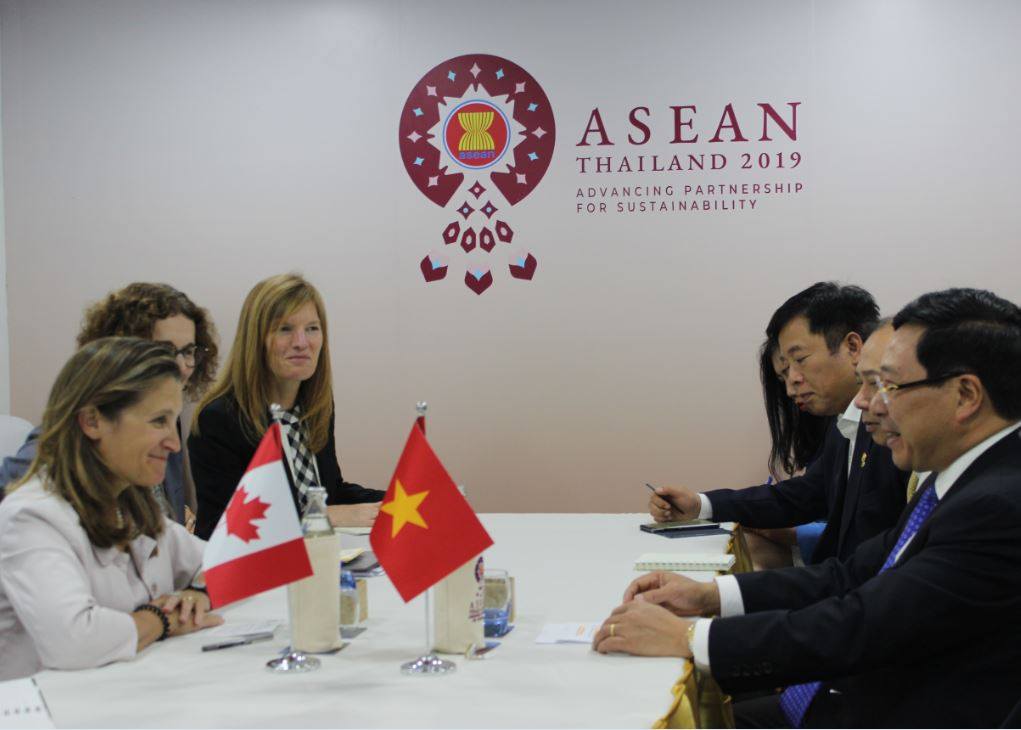

Minister Freeland and Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs of Vietnam, Pham Binh Minh, met at the ASEAN meetings and underlined the strong ties between Canada and Vietnam. Source: Global Affairs Canada’s Facebook Page

Even before the pandemic, international companies with manufacturing in China and the privately-owned Chinese companies were moving their production base to Vietnam, among other locations in Southeast Asia. The key decision in moving manufacturing from one country or region to another includes the cost-benefit analysis, ease of doing business in a country, and the political stability – among other things.

Guest Author: Aadil Brar

The COVID-19’s most disruptive impact has been on international travel and supply chains. The first supply shock of the pandemic was meted to the medical supplies. This has followed disruption to all of Canada’s international supply chains.

The world of policy experts and journalists has been abuzz with chatter about what the post-COVID-19 trade will look like. One thing that can be said for certain is that COVID-19 is bound to transform global trade.

President Trump’s escalation of trade tensions with China, Canada, the European Union, and other countries has stirred the debate about supply chains and global trade. The COVID-19 pandemic and China’s actions during the crisis has ensured that major economies will look to reduce supply chain dependence on one country – China.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed serious vulnerabilities in Canada’s supply chains. The shortage of personal protective equipment for front-line doctors, nurses and medical workers has topped the news across the Canadian media.

Canada has taken some steps to ensure steady supply of essential goods from international markets during the pandemic. Minister Mary Ng announced that Canada has signed agreements with Australia, Brunei, Chile, Myanmar, New Zealand, and Singapore to ensure “open and connected supply chains throughout the pandemic”. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau spoke to India’s Prime Minister Modi on the “vital need to keep supply chains open for medical equipment and other critical supplies, as well as the need for increased international cooperation to accelerate the development of diagnostics, treatments, and potential vaccines”

Ottawa was swift to announce measures to secure Canada’s critical domestic industries from being bought out by state-owned enterprises or individuals with ties to a foreign government. Similar measures have been announced by Australia, Japan, and India. Because of COVID-19, 40 economies have imposed export restrictions on medical supplies and 150 countries have imposed international and domestic travel restrictions.

Prior to the pandemic, Canada was working on diversifying its trade partnerships through new alliances and agreements. In 2017, the Comprehensive Economic Trade Agreement with the European Union, and in 2018, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, entered into force. The impact of both these agreements has been mixed so far, but these agreements have laid the foundation for comprehensive collaboration between Canada and other countries in Asia.

“Canada needs to build alliances with like-minded countries to maintain open international supply chains. This could mean mutual strategies to address threats among the alliance, and pledges of assistance to individual members. Such alliances would supplement and work in concert with existing and future trade agreements” Daniel Schwanen and Glen Hodgson of the C.D Howe Institute said in a memo.

Even before the pandemic, international companies with manufacturing in China and the privately-owned Chinese companies were moving their production base to Vietnam, among other locations in Southeast Asia. The key decision in moving manufacturing from one country or region to another includes the cost-benefit analysis, ease of doing business in a country, and the political stability – among other things. The rising cost of labour in China has marked up the cost of production in recent years, making it viable to seek better options for a manufacturing base.

Moving the manufacturing base from China to Vietnam hasn’t been a smooth sail, the Wall Street Journal reported, “The specialized supply chains that made China a production powerhouse for smartphones and aluminum ladders and vacuum cleaners and dining tables are nowhere near as developed in Vietnam.” Despite the challenges, Vietnam and India still offer economies that can be reliable sources of supply chain diversification for Canadian companies.

On September 10 2019, the conclusion of the exploratory discussion on the Canada-ASEAN Free Trade Agreement was announced in Bangkok. The group of ASEAN countries together make up as Canada’s sixth-largest trading partner. ASEAN countries include: Indonesia, Thailand, Singapore, Malaysia, Philippines, Vietnam, Brunei, Cambodia, Myanmar, and Laos.

According to a World Bank report released earlier in April, Vietnam is the only country in the ASEAN group of countries that can maintain positive GDP growth of +1.5% despite the pandemic bringing global trade to near collapse.

Wayne Farmer of the Canada-ASEAN business council said “If Canada signed a deal with ASEAN, it would have access to a market of more than 642 million consumers with a combined economy of $2.8 trillion. With an average annual GDP growth of 5.4% in recent years, ASEAN is now the fifth-largest economy in the world and on track to become the fourth-largest by 2030, after the U.S., China, and the European Union.

According to a survey by the Asia-Pacific Foundation in 2018, 63% of Canadians support an FTA with ASEAN, which is up from 40% in 2014. In 2018, Canada’s two-way trade with Vietnam was at $6.46 billion.

About 66% of the Canadians support an FTA with India, according to the same survey by Asia Pacific Foundation.

China will remain the hub for manufacturing technological products such as Apple iPhones and MacBook computers because China still offers the best options to manufacture those goods. Automation of manufacturing will reduce further the dependence on labour in China, making it feasible for companies to stay put in the country. However, the COVID-19 pandemic and a potential second-term for US President Trump will grow the trade uncertainties and accelerate the movement of companies from China to other locations in Southeast Asia and South Asia.

It was Nixon’s visit to China that paved the way for a new relationship with the US. Similarly, Former Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau’s visit in 1973 shifted the gears of Canada’s relationship with China. Trade agreements can only lay a roadmap for Canadian companies, but it will take action by the political leadership for them to actually walk on it.

About the Author: Aadil Brar is a freelance journalist. His reporting has appeared in the BBC, the Diplomat, Devex, and other publications. His work can be view at www.aadilbrar.com. You can follow him on Twitter at @aadilbrar.