Image credit: Remko Tanis

By Zhouchen Mao

This article is published as part of IPD’s China Strategy Project.

On December 4, China’s State Council Information Office published a White Paper entitled “China: Democracy That Works”, offering a different notion of democracy called “whole-process people’s democracy”. The term first emerged in 2019, claiming “all major legislative decisions are made through democratic deliberations to make sure the decision-making is sound and democratic”. In a tacit acknowledgement that Chinese democracy differs from the liberal conception, the paper suggests that liberal democracy isn’t the only kind and that China’s democracy is adapted to its own tradition.

The White Paper’s release, which was timed just days before the Summit for Democracy, has been dismissed by some Western political leaders and analysts, while drawing criticism from outside observers. A few have focused on the domestic realm and maintained that China’s attempt to redefine democracy is to shore up the legitimacy of both the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the political system as Beijing faces a deteriorating external environment. But Beijing’s promulgation of its own brand of democracy is not a mere response to the US-led Summit for Democracy or simply domestically driven. It should instead be read in the wider context of China’s contestation of the international normative order that is often at odds with its own distinct preferences. To do so, officials and scholars are calling for greater participation in and contribution to the global discourse on democracy, as well as an expansion of China’s discourse power (话语权) – defined as one’s ability to shape the international agenda and acquire some form of acceptance of its values and ideologies.

But more importantly, the Western response that emerged following the White Paper’s publication – largely triggered by the contrasting meaning from the widely accepted Western-style democracy – reflects a broader issue rooted in the fundamental principle of justice in global governance. The centrality of global justice focuses on how stakeholders have equal opportunities to critically engage in normative contestation and how a formal agreement on normative content can only materialise through this process. Ultimately, standards, principles, and ways of judgement should be critiqued and counter-critiqued to incorporate multiple, equally valid meanings. This way, norms that emerged from this procedure would have greater legitimacy and global governance would become more effective. But far too often, non-Western countries including China are being relegated to the role of a simple recipient and deprived of their agency to act as a norm settler. In other words, the current normative order is essentially a project dominated by a few developed countries.

The Right to Speak

So why is China contesting norms like democracy?

First, there is a consensus in Beijing that whoever controls the words rules the world. The West’s dominance of the normative order largely derives from its ability to convey and maintain the liberal norms and values that command how this order is run. Despite the rapid growth in its material power, Beijing still lacks discourse power to truly become a norm settler and provide equally valid meanings on ideals that underpin a more inclusive and pluralistic form of global governance. Since 2017, President Xi Jinping has emphasised China’s commitment to actively partake in building global governance with Chinese characteristics. In practice, part of this process involves the (re)construction of normative understandings based on Beijing’s own ideals, with the intention to also contest the universal applicability of Western values and ideas. Moreover, China’s attempt to redefine democracy projects a much more confident China in propagating terminologies that carry normative impact, and a leadership that is convinced the “East is rising and West is declining” and that “time and momentum are on our side”.

China’s discourse power has been encapsulated by narratives such as a China Solution (中国方案) and “Building a Community of Common Destiny for Mankind”. Both narratives signalled China’s intention to reclaim its rightful place and willingness to (re)shape various aspects of global governance by advocating “Chinese wisdom” and a more localised approach in resolving global challenges rather than a one-shoe-fits-all model.

Unlike material power that can be measured in terms of economic and military resources, a state’s discourse power can be assessed through the normative impact of discourse and its ability to gain normative legitimacy. Examples such as the Chinese Dream (中国梦), a major slogan associated with national rejuvenation since 2012, show the limits of Chinese discourse power. Despite concerted efforts by Beijing to promote a discourse of respective national dreams in the developing world – an African dream, a Ghanian dream, to name a few – and build international legitimacy, it has found little positive reception.

Second and relatedly, by expanding its discourse power and engaging in discursive contestation over norms championed by the West such as democracy, China is exercising a growing capability that is commensurate with its power. As a great power second only to the US, it is anticipated that Beijing is acting in correspondence to its global status by increasingly focusing on “guidance diplomacy” (引导外交) under which Chinese foreign policy is no longer solely economy driven, but also concerns with national image, discourse power, and contributions to public goods and humanity. Under this context, Beijing underscores both the importance of upholding core national interests and the prospect to “guide” (引导) the reforms of the global governance system with reference to the concept of fairness and justice. Henceforth, discursive contestation is one of the main tools used to achieve the end goal of reforming the current system by contesting the applicability of norms such as democracy, the rule of law, and human rights.

Third, discursive contestation of democracy helps delineate the Chinese conception as distinct from, if not superior to, that of the West. It also epitomises a form of pushback amid escalating ideological competition with the US that has often framed authoritarian China as a major threat to democracy. Beijing – rightly so – views the Summit for Democracy as another of Washington’s attempts to build an anti-China coalition – following the Quad and AUKUS – by strengthening relations with allies and partners to contain growing Chinese power and influence. In pushing back against the binary distinction between democracy vs. autocracy, Beijing is also seeking to reconstruct the current narrative towards good vs. bad governance by magnifying its “people-oriented” philosophy where the CCP claims to serve the interests of all people.

What Exactly is Chinese Democracy?

The term democracy is a difficult concept to tackle in China – albeit not a new one. Although democracy almost appears as an antithesis to the country’s one-party rule where the CCP does not allow open elections and punishes those who openly call for multiparty rule, democracy has indeed been embedded in Chinese history for more than a century. Chinese author Liang Qichao first introduced the concept of democracy which was translated to 民主, literally “people” (民)and “leader” or “ruler” (主), i.e. ruler of the people. The origin of the current Chinese government’s democratic claim can be traced back to its Marxist-Leninist ideological and institutional DNA where, despite President Xi’s centralization of power, democratic centralism – an arrangement that centralizes state power in the hands of CCP and party’s power in hands of the top leader – represents the core principle of Chinese socialist democracy.

In modern-day China, democracy is often associated with the quality of governance and guided by a “people-oriented” philosophy, rather than the procedures of democracy such as general elections. For the CCP, there is an equivalence between development and democracy where a “social contract” is created based on the Party’s ability to bring about development. As Vice Foreign Minister Lu Yucheng previously noted, whether a country is a democracy or not should be judged based on the government’s responsiveness to its citizens, highlighting China’s success in poverty reduction, economic modernisation, and management of the COVID-19 pandemic. Such understanding of democracy is also echoed by President Xi’s remark on “whole-process democracy” as the top leadership appears to define governance using the Confucian philosophy of “benevolent” (仁), which refers to governing based on care for the people by improving living standards and providing economic opportunities.

Pragmatism in Canada?

The Chinese conceptualisation of democracy is highly unlikely to resonate with Canadians given our special relationship with Washington and our position within the Western world. And this comes as the public mood is agitated and negative, with recent polls indicating that a growing majority of Canadians see China unfavourably. There is plenty of scope for friction with China, particularly when it comes to media freedom and human rights. Though other issues have emerged in recent years. Ongoing tensions in the Taiwan Strait, Beijing’s crackdown in Hong Kong and Xinjiang, China’s detention of the two Michaels and subsequent trade actions have all contributed to hardening Canadians’ perceptions. In Parliament, the opposition Conservatives have called for close coordination with like-minded countries to tame the perceived existential threat from China against Canadian/Western institutions and values.

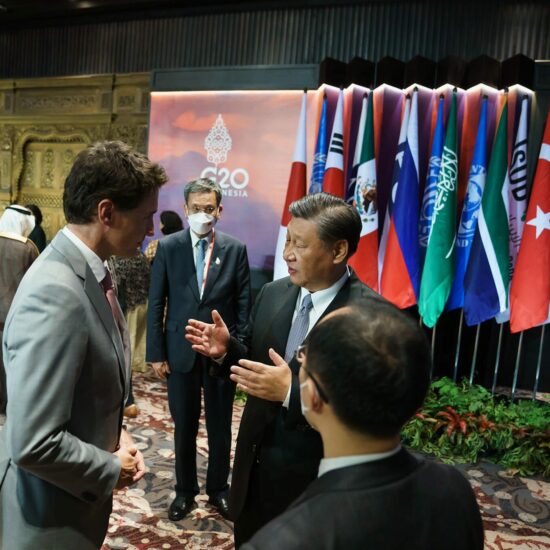

Despite the hawkish drift in China policy across the Western world, to which Canada is not immune, there remains some lack of clarity as to what Canada’s China policy is. Unlike the US who sees China not just as a revisionist power, but also a strategic competitor, the Trudeau government has employed a mixture of competition and cooperation when dealing with the country. For Canada, it is important to recognise that China is not a peer competitor or a major security or military threat. Beijing is a far lesser threat to Canadian national security than the rise of far-right wing groups, as witnessed in recent nationwide COVID-related protests. The broader securitization of relations with China in the West can be highly problematic, particularly when this trend permeates to fields such as education, academia, and culture that previously allowed for cooperative and positive interactions. Interpreting issues primarily or exclusively as a security concern would result in significantly different risk assessments that could undermine appropriate policy responses given that there are only a limited number of actors authorised to deal with an issue, which in turn hinders policy debates, while casting the positions of advocates as “malicious”. It is inevitable that shifting attitudes towards China in the West will continue to push Canada to make a binary choice and lean to one side. But Ottawa should embrace a pragmatic approach that sees China as it is, not the way we want it to be. This, in turn, would also require the Canadian government to reckon with the changing distribution of power from West to East. That is not to say we should blindly engage with China and disregard the significance of our relationships with the US and other Western partners. Rather, Canada’s approach should be clear-eyed and cautious, competing where necessary, and focusing on areas where we can and should contribute such as forging a global governance system that is more effective and more inclusive by participating in normative contestation and bargaining that will counteract biased perspectives and strengthen the legitimacy of norms.

Going forward, greater attention to China’s expansion of discourse power is needed. For the political elites, being heard and listened to constitutes a major aspect of China’s ascent to great power status. Meanwhile, the concept of democracy will remain contested although a plurality does not signify failure, but rather fulfils the quest for alternative understandings.

Dr. Zhouchen Mao (@mao_zc) is Senior Analyst for Asia Pacific at AKE International and an Associate Fellow at IPD.