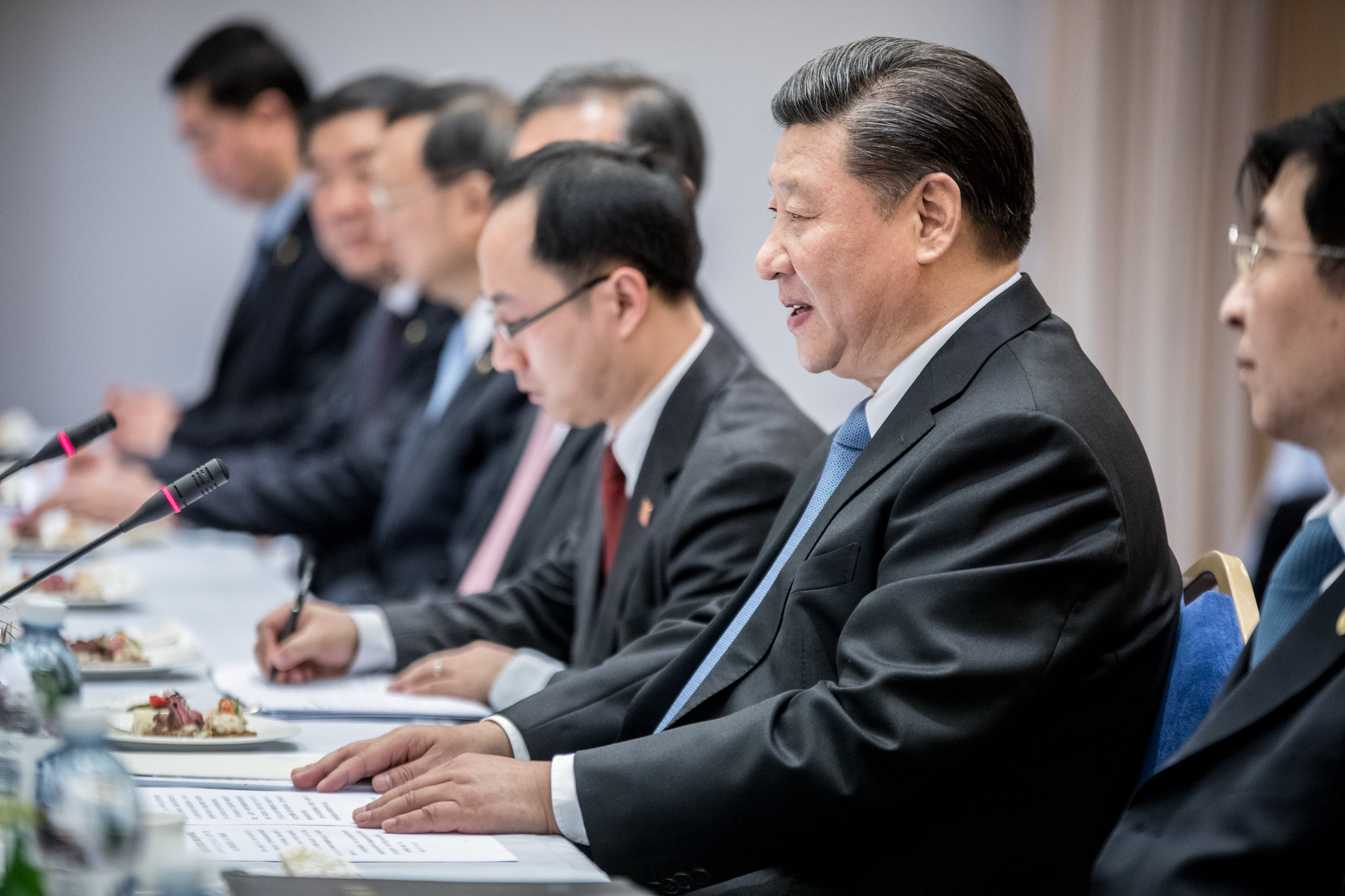

Image credit: Finnish Government

By José Niño

During the United States’ so-called “unipolar” moment of the 1990s, the prevailing wisdom was that the world entered an “end of history” moment where Western liberalism was destined to be the universal standard of governance worldwide. To many policy-makers in the West, the collapse of the Soviet Union meant liberal democracy and market-based economies could now flourish worldwide.

To be sure, there were laggards to this liberal triumph such as China, Cuba, and North Korea, but the overriding assumption was that the march of progress would be inevitable. China, especially, it was believed, would liberalize through the American policy of engagement and increased economic intercourse with the U.S. The logic at the time went as follows: Increased trade with China and its integration into the global economic order would motivate Beijing to liberalize not just in economic terms but also politically. To help along this supposedly self-fulfilling prophecy, U.S. policymakers granted Beijing permanent normal trading relations (PNTR) status and supported its accession into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in the early 2000s.

With the break-up of the Warsaw Pact and the expansion of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) into Eastern Europe, the conventional wisdom in Washington also professed the end of the ‘sphere of influence’ politics. Liberalism’s perceived triumph during the Cold War convinced many Atlantacists that geopolitical conflict would simply vanish and permanent peace would be achieved in our time — once all nations of the world inevitably became liberal democracies.

In reality, history did not end. War did not disappear. And, many countries resisted democratization. Some like Russia even reversed course, rejecting the liberal paradigm in toto under Vladimir Putin. Those false, if lofty, liberal assumptions were further proved hollow when Russia asserted itself in its traditional sphere of influence in Georgia (2008) and Ukraine (2014). In fact, Russia has been engaged militarily in the latter country for eight years to repel what it perceives as Western encroachment into its sphere of influence.

The Russian redline on Ukraine culminated, towards the end of February, in a large-scale incursion to demilitarize and impose neutrality on Ukraine. That tragic war is on-going with devastating impact on civilians, but it is a reminder that the regional security dynamics and distribution of power matter: Russia views Ukraine as an essential and non-negotiable component of its sphere; and as a regional hegemon, Moscow has the power to bend Kiev to its will and will do so, no matter what Washington or NATO demand or how they frame the conflict.

Accepting this reality — that regions matter and have historically-rooted hierarchies — is not to endorse the spheres of influence, but rather to engage with the world as is. The same situation applies in East Asia vis-a-vis China and Taiwan. While Beijing has not taken kinetic action thus far, it has reiterated its unwavering desire to unify Taiwan with the mainland. It has even stated its willingness to employ military force against Taiwan should it formally declare its independence. Like Russia, China is poised to eventually challenge the status quo within its sphere of influence.

Moreover, China has taken stronger stances towards its maritime claims in the East and South China Seas, finding itself at loggerheads with countries such as Japan, the Philippines, and Vietnam. As the traditional guarantor of security in the Asia-Pacific region since the end of World War II, the U.S. has invariably gotten more involved in these disputes as it gradually makes its “pivot to Asia.”

With Washington increasingly ramping up its military presence in Asia and building a balancing coalition to contain China, there is now heightened speculation about a potential hot conflict between the U.S. and China. Certainly, confrontation between these two nuclear powers is not inevitable, but to de-escalate tensions and reach a point of peaceful coexistence will require some strategic empathy on Washington’s part — something that Atlanticists have ignored for the past 30 years with regards to Russia’s valid concerns about NATO’s expansion into what Moscow considers its sphere of influence.

Analyzing China’s history offers a better understanding as to why China desires a larger role in shaping security affairs in the Asia-Pacific region. From the latter half of the 19th century up until World War II, China found itself in a vulnerable state — open to aggression by external actors. This “century of humiliation” is still seared into the memory of many Chinese foreign policymakers. Some of the most notable instances included:

- China’s defeats during the Opium Wars which opened the door for European powers to carve out their own spheres of influence in China.

- The First Sino-Japanese War in which China was compelled to recognize Korea’s independence, hand over the island of Formosa (now Taiwan) to Japan, and to pay Japan a stiff indemnity.

- The Eight-Nation Alliance intervention that put down the Boxer Rebellion, interpreted as a further demonstration of China’s inability to keep foreign actors from exercising power and coercive actions in its territory.

- The Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931 which resulted in the establishment of the puppet kingdom of Manchuko. This later became the launchpad for Japan’s subsequent military campaign against China during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945).

The important point here is that irrespective of the ideology that underpins a particular regime — be it authoritarian or liberal — maintaining security over its domain is a chief concern for any state. China’s growing assertiveness within Asia is also to be understood within regional security complex theory, which posits that states in a given region have closely linked national security concerns that cannot be so easily separated.

China’s security interests are interlinked and in some instances even aligned with its neighbors. For example, China and its counterparts in Southeast Asia will have to confront piracy and other transnational threats that require security cooperation among that region’s nations. Security interdependence is an inevitable feature of international relations and states in a particular region pursue their security interests within regionally based clusters.

As the world shifts to multipolarity, revisionist great powers like China or Russia will pursue foreign policies that could antagonize their smaller neighbors, challenge Washington, and disrupt the liberal international order underwritten by the U.S. and its allies. Nevertheless, such realpolitiking has long been a hallmark of great power statecraft: there is nothing uniquely evil or irrational about it. The North Atlantic would therefore benefit from heeding history and abandoning a moralistic framing which ignores realism and prudence.

Under the Monroe Doctrine, the U.S. itself used conquest and territorial aggrandizement to establish itself as a great power throughout the 19th century. In so doing, it established itself as a regional—or rather continental— hegemon, pushing out foreign competitors and ensuring that no great power could ever interfere in or set up a military presence around America’s periphery. North Atlantic decision-makers must recognize that as China develops economically, it will also strengthen militarily. As a result, it will come to assert itself in its historical area of dominance like countless other civilizational states have done so in the past.

To be sure, the US has legitimate grievances with China regarding its trade practices and acts of espionage committed by Chinese nationals within its shores. These are matters that will require uncomfortable conversations and bold reforms to address. That said, using the Atlanticist foreign policy formula of megaphone diplomacy, moralistic rhetoric, and coercive sanctions that ignore the redlines of rivals and spurn compromise — a model that has failed repeatedly in the Middle East and elsewhere — against a rising China is to court escalation and unleash potentially catastrophic kinetic conflict. This approach failed against Russia. It will fail even more against China.

Hard-nosed realism, bereft of overly ideological presumptions, is the most optimal course in addressing the China question. A prudent approach, centered around strategic empathy and clever diplomacy, should be the ultimate North Star in navigating the uncharted waters of great power competition in the 21st century.

José Niño is a freelance writer and contributor to Mises Institute. He holds a Master’s Degree in International Relations from Universidad de Chile and a B.A. in Government and History from the University of Texas at Austin.