Image credit: Mykhailo Palinchak

By David Carment and Dani Belo

An abridged version of this article was featured in iPolitics.

The clouds of war have gathered over Eastern Europe as the conflict in Ukraine threatens to engulf members of the EU and NATO in a direct confrontation with Russia. In this article, we argue that neither Russia nor the United States are willing to make substantial concessions, locking them into a path-dependent outcome that will result in increased regional instability, deeper divisions within NATO and an uncertain future for Ukraine. We review the interests and actions of both the United States and Russia as well as members of the EU, Ukraine and Canada. We draw attention to four distinct conflict scenarios which are ranked from highest to lowest probability moving left to right in the table below. We conclude by arguing that a long-term path to stability starts with regional actors re-asserting their role as conflict managers.

Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelensky recently announced to the people of Ukraine that war is unlikely. Zelensky’s statement creates a window of opportunity where all parties can take a deep breath and consider alternatives to war. But it is clear, neither the US nor Russia are operating from the same assumption. Major concessions that could lead to a de-escalation in tensions appear increasingly improbable. Not only has the US rejected Russia’s demands, but the administration is also preparing a major arms deal for Ukraine along with a massive sanctions bill. Congress will likely approve both with near-unanimous support next week to coincide with America’s written response.

Path dependency shows up in other ways. Several of Joe Biden’s senior and most important State Department staff are among those uncomfortable with how the Ukraine crisis has been managed since 2014. Their most prominent concerns are tolerance for Russia’s pre-emptive takeover of Crimea along with its covert support for separatists in Donbas, both of which happened under their watch.

Eight years later these senior officials, whom some might describe as “intervention entrepreneurs” are looking to complete “unfinished business.” A firm response to Russian election interference which Democrats believe tipped the 2016 Presidential election outcome in favour of Republican Donald Trump might be an additional motivating factor.

Key personnel carryovers from the crisis in 2014, include Biden himself, along with Antony Blinken, Jake Sullivan, and Victoria Nuland all of whom were personally entangled in the Maidan protests and the fallout from Kyiv’s calamitous political collapse. Nuland in particular is focused on escalation with Russia as she perceives the threat of invasion of Ukraine by Russia as a constant and imminent probability. This continuity can be understood by reviewing her various testimonies to the United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations from 2016 to 2021. The confusion in Nuland’s analysis is that, as we now know, escalatory tactics lead to greater regional insecurity and fear of war, not deterrence.

Based on America’s actions so far it appears the Biden administration is trying to shift world opinion away from a multiparty peace process, focused on a relatively small sub-region within Ukraine to pan-regional crisis management, with the US leading the charge. Though American policymakers support alternative peace processes in principle, these processes have not figured prominently as part of the US administration’s current strategy. These processes include the Minsk II Protocols, the Normandy Format and the Trilateral Contact Group where the US is essentially relegated to the sidelines. In brief, America’s unstated goal appears to be balancing a desire to disrupt the status quo such that rapprochement between Russia and Europe remains out of reach while minimizing political fallout at home.

On the one hand, Joe Biden, a President whose popularity is polling at 40 percent stands to gain little from dragging the US into yet another regional conflagration. On the other hand, State Department announcements are not centred on making concessions to Russia but on enabling a Ukrainian offensive to retake territory currently claimed by separatists and on Ukrainian willingness to wage an insurgency in the event of Russian intervention.

In regards to supporting an insurgency, the US usually throws its support behind those countries that have the materiel and willingness to fight. That is why it is extraordinary to see the Biden administration publicly admit they are focused on supporting an insurgency against Russia while arming it at the same time. The US has typically supported insurgencies more covertly or at least through subtler means.

There is no guarantee that key allies are on board with such a strategy. When it comes to supporting local wars, the US always has a strategic plan but as Afghanistan shows, the lack of coordination and differences among allies on how to execute it made the mission ripe for failure and exploitation. For example, Germany refused to label the country’s mission in Afghanistan a war, focusing its attention on peacekeeping and reconstruction projects. In contrast, Washington was clear that its primary mission was security threat elimination. These differences in approach did not result in an effective division of labour. Rather, those differences stretched the ISAF coalition so thin that it could not effectively address either of these challenges.

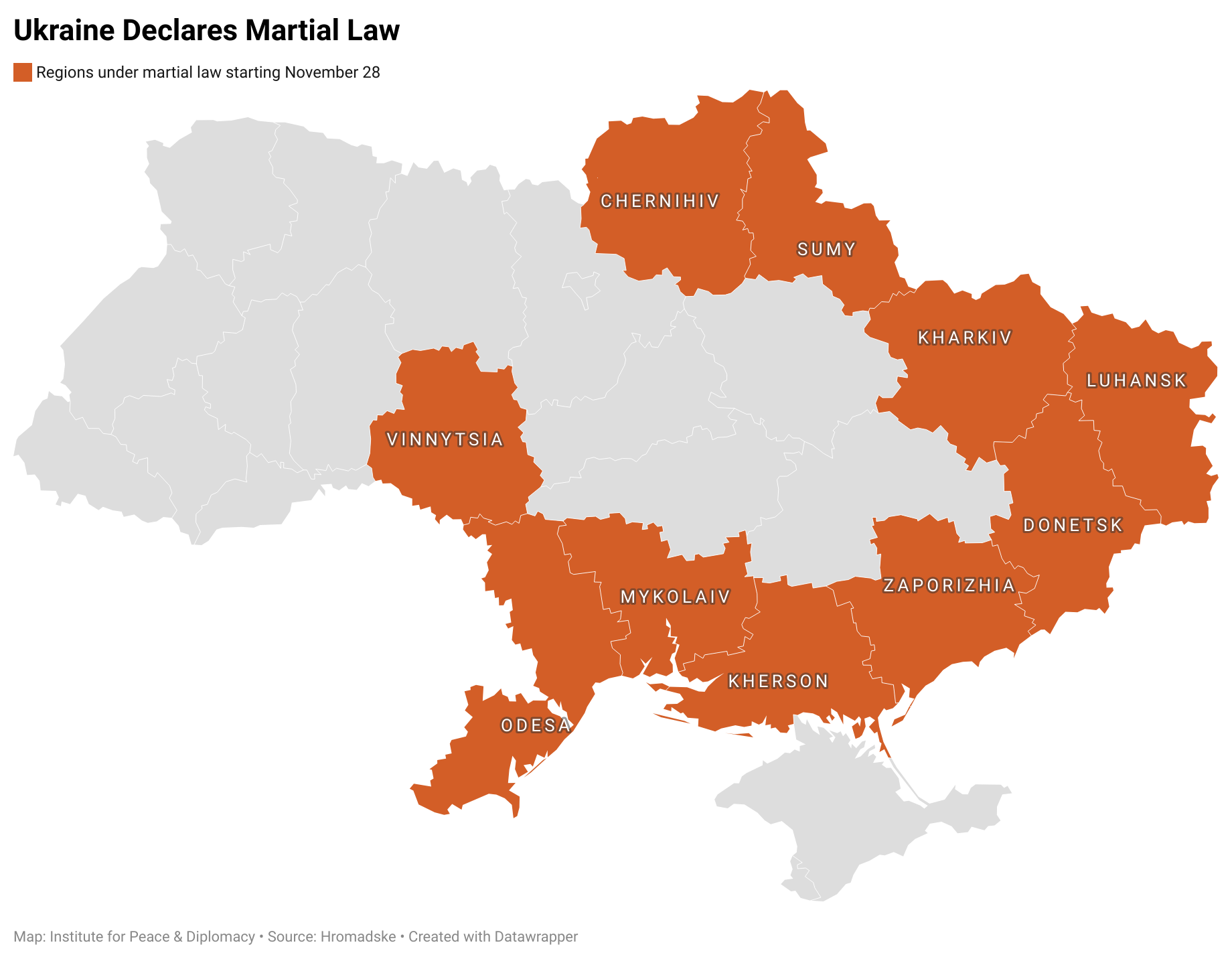

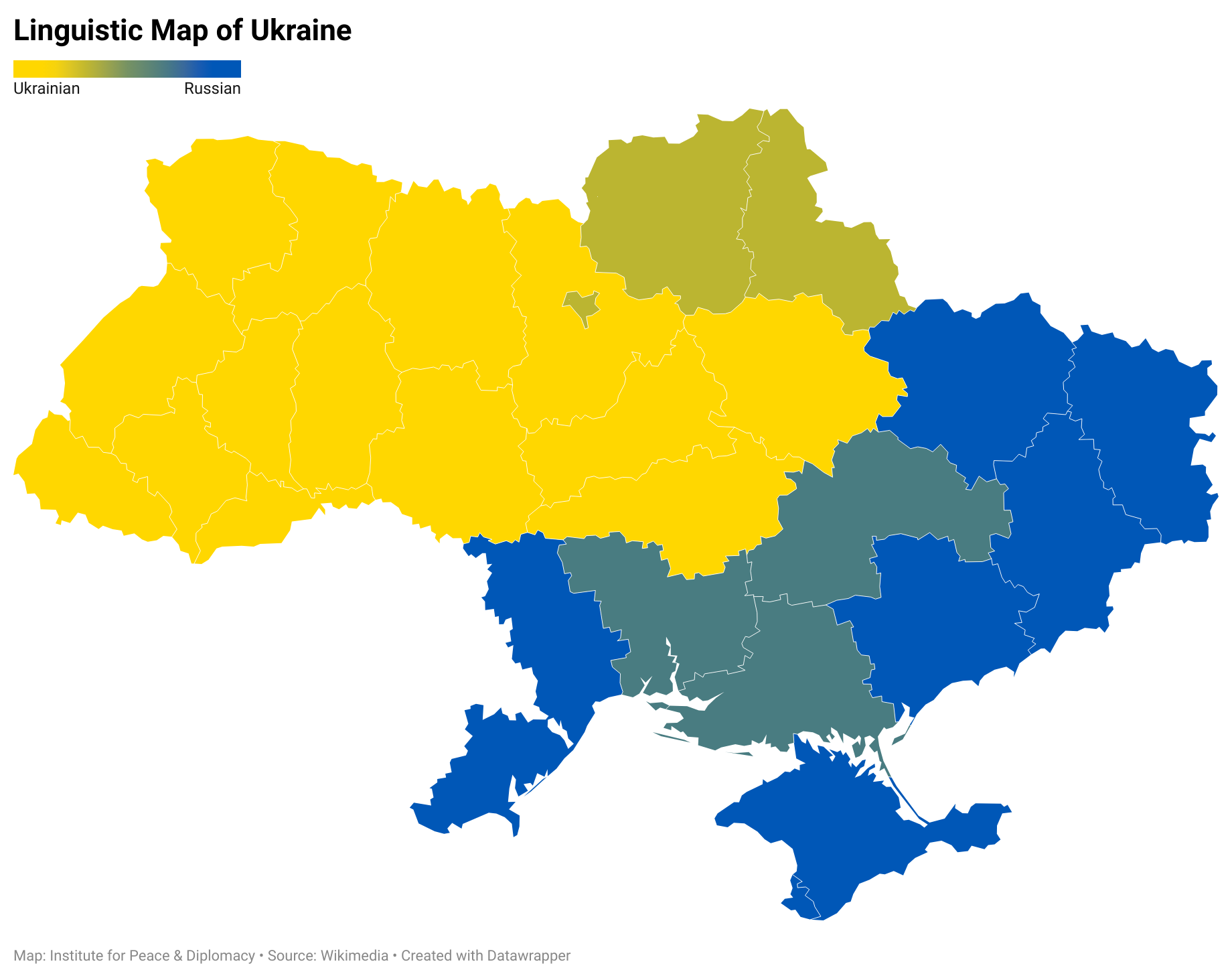

Neither warfighting nor insurgency are appealing outcomes for Ukraine. Despite claims to the contrary, Ukraine is a divided country. As we have written elsewhere, Kyiv’s efforts to counter Russia’s grey-zone operations in Donbas overlap with the curtailment of minority language rights and increased social exclusion within Ukraine proper. When Petro Poroshenko declared martial law in 2018, only those oblasts in which the Russian language figured prominently were targeted. Maps 1 and 2 below illustrate this. It is often forgotten that in the immediate aftermath of Maidan, Odessa and Kharkiv, among others, considered breaking away from Kyiv. An estimated 1 million Ukrainians instinctively fled to Russia.

To be clear, the Maidan was supposed to be about uniting all Ukrainians—regardless of ethnic identity, religion or language-within a single nation. Controversial language and memory laws have undermined that objective. These controversies have successfully contributed new fodder for Russia’s soft-power incursion into Ukraine’s media space under the guise of an anti-Nazi sentiment among Russia’s diaspora. The simple fact is that Ukraine is now more than ever vulnerable to exploitation and susceptible to outside influence from both West and East because it is weak. Its weakness invites outside involvement rather than the other way around.

Discussion of insurgency is also troubling because Ukraine as a polity is unlikely to weather the storm unless third-party efforts are taken to protect its minorities. It is ironic that under America’s direction NATO became the primary tool for protecting minorities in the Yugoslav war and was the key reason why NATO got involved in the conflict in Bosnia, took action in Kosovo and gave long-term support to Europe’s Stability Pact throughout southeast Europe. Today it appears America’s policymakers are prepared for the possibility that Ukraine may well be at war with itself, which is a departure from Washington’s focus on Russia as the primary conflict initiator. For a country that has 15 nuclear generating stations scattered across potential hot zones (several of which are among the largest in Europe), war has unthinkable regional consequences such as targeted attacks on these generating stations.

For its part, Canada has repeatedly demonstrated that, though it supports Ukraine, it has only a limited interest in resolving current tensions. This is not an essential war for Canada apart from any domestic pressures that might be brought to bear, sunk costs in terms of development assistance and an increasing military presence. Obvious commitments come from Canada’s membership in NATO more than any fundamental belief that protecting Ukraine is vital to Canadian interests.

Indeed, from Chrystia Freeland’s tenure onward, Canada’s Foreign Ministers have shown only the very limited diplomatic capacity to engage with Russia directly, save for a meeting that Marc Garneau held with Foreign Minister Lavrov in the spring of 2021. This may have been a meeting that, perhaps, fell outside the PMO’s purview and for which Marc Garneau may have been chastised.

Canada is part of a small group of states who have not formally expressed a willingness to address underlying rifts with Moscow. Despite his claim that a diplomatic solution is the best way forward, Justin Trudeau has never discussed the conflict with Vladimir Putin except on the sidelines of various summits such as the G20. Indeed, the UK, the US and Canada have chosen to work outside of NATO in some important ways. For example, all three are part of the Multinational Joint Commission which initially, at least, was intended to introduce professionalism among Ukraine’s forces. Canada joined the Commission when Jason Kenney served as Canada’s Defence Minister despite concerns over corruption and profiteering in the Ukrainian military. Such is the depth of the relationship between Washington, Ottawa, London and Kyiv today, that Ukraine’s Defence Minister has repeatedly asked for lethal weapons along with troops to fight alongside his own. Should Canada comply, the government could find itself undermining its own Aid Accountability Act in which human rights are front and centre.

In essence, there is a looming rift within NATO on how to engage Russia. Washington and London are set on militarized deterrence and the arming of Ukraine at the expense of diplomacy. The Joint Commission gives them a way to both circumvent and force the hand of allies who are reluctant participants in this conflict. The paradox is that ongoing escalatory actions by a handful of countries undermine both regional security and deterrence. There have been an estimated 3000 flashpoints since the conflict began involving both sides. Each of these has the potential to escalate to war. For example, in 2018, Russia sent nuclear-capable bombers to Venezuela at a time when the Trump administration floated the idea of toppling Maduro. Today, Russia has made it clear that it has sufficient reason to continue these missions within America’s sphere of influence, given what it sees as deliberate and provocative acts that threaten Russian security.

Canada’s deployment of special forces to Ukraine can be understood in this context. The initial narrative was that Canada would support Kyiv’s fight in case of a Russian invasion. This means that Canada’s special forces, although small in number, are a form of lethal aid. The second narrative has been that these forces will assist the evacuation of Canadian diplomatic personnel. That soft exit appears increasingly likely. The deployment of troops based on the first justification places Canadian troops in a dangerous situation for nothing more than political symbolism. In other words, a small team of Canadian special forces does little to shift the balance of power in favour of Kyiv or NATO if Moscow decides to conduct targeted operations against Ukraine.

From a Canadian perspective, given that it is weighing increasing arms shipment to Ukraine, crisis escalation carries few long-term security benefits. If anything there will be long-term negative consequences for Canada-Russia relations in the Arctic where there is a shared interest in economic cooperation. Canada’s international standing is unlikely to be enhanced. That is because Canada is not part of the Normandy Format, nor the Trilateral Contact Group. It has not been an active participant in the Minsk II talks and its Ministers have rarely referred to the OSCE which brokered Minsk II. Melanie Joly, Canada’s current Foreign Minister characterizes sanctions as a tool for de-escalation (which they are not). Global Affairs Canada appears to be not mandated to engage with Russia directly.

A key contributor to crisis escalation has been the UK’s Prime Minister Boris Johnson. Under his leadership, the country is flying arms shipments to Ukraine, which mostly consist of anti-tank weapons (bypassing German airspace in doing so). Although the 2000 units shipped so far cannot shift the balance of power in favour of Ukraine, looking at this from Moscow’s perspective, such actions send a signal confirming its suspicion about the West’s intentions to undermine its security interests. Moscow’s Ambassador to Germany articulated the negative impact of such arms shipments on trust-building in an interview with NordKurier. This clear signalling from Moscow regarding its ‘red lines’ has not so much gone unheard, it has been deliberately ignored.

Similarly, in December 2021, Joe Biden quietly authorized a $200 million aid package to Ukraine, which involves weapons delivery and training of Ukrainian security forces personnel. The first tranche of weapons arrived on January 22, 2022. Moreover, the United States committed to sending radar systems and maritime equipment to Ukraine. These arms shipments which include lethal weapons may increase Kyiv’s capacity to fight, but they are insufficient to shift the balance of power decisively to win a war against the separatist territories or Russia. In other words, these weapons supplies may embolden Kyiv to act against the separatist territories thereby incurring greater casualties in a campaign it will likely lose without third-party support.

Indeed, like his predecessor Petro Poroshenko, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky may feel compelled to declare martial law, resulting in the suspension of habeas corpus (this is Scenario 2 in the table below). Martial law may be undertaken to prevent any ‘shaping operations’ of the local political landscape by Russia ahead of any military actions. More ominous perhaps has been CIA training of Ukrainian Special Forces who have been tasked to be the disruptive search and destroy element within a widening covert strategy. Considering that 14,000 Ukrainian citizens have been killed in this conflict one can easily imagine a scenario where those numbers multiply fivefold within a very short time span (this is Scenario 3 in the table below).

For Russia, the higher costs of war are unlikely to affect Moscow’s final decision on Ukraine (Scenario 4 in the table below). Under this scenario, Russia may pursue the occupation of the ‘Novorossiya’ territory in southeastern Ukraine, thereby establishing a land-based bridge to Crimea. Therein, the value of NATO remaining outside of Ukraine is much greater for Russia than the value of Kyiv’s alliance membership for the West. The Germans and the French understand that perspective. The Americans have chosen to ignore it as their most recent response to Russia’s ‘red lines’ make clear.

A fundamental impact of the change in American resolve to confront, rather than accommodate, is clear. If Russia is indeed contemplating actions in Ukraine based on several crossed ‘red lines’, then the war materiel and training supplied by the West are only making these operations more imminent while Ukraine is weak. This is the ‘window of opportunity’ Scenario 1 in the Table below. In other words, Russia has an incentive to strike before Ukraine becomes stronger through the incorporation of these arms, radar systems and lethal weapons into its armed forces.

As noted, Washington is also committed to supporting an anti-Russian armed insurgency if war does break out. But recent evidence clearly shows insurgencies have ended disastrously for the US in Iraq, Libya, Syria, and most recently Afghanistan. These campaigns fail to support democratic national governments, protect human rights, establish robust institutions, and enable radical groups to seize power. In effect, the US will walk away relatively unscathed, with Europe left to pick up the pieces. It was, after all, Europe and Middle East nations who were faced with destabilizing refugee flows that arose from America’s missions in Syria and Iraq and its targeted bombing campaign in Libya.

From a conflict management perspective, there are several points to consider. First, support for insurgencies in ethnically divided societies generally results in the escalation of inter-communal violence, with little to be gained geopolitically for the external interveners in the long run. The permissive conditions for violence onset have already been created by Kyiv when it adopted several policies to curb minority language and education rights affecting several communities in Eastern and Southwestern Ukraine. Second, internal conflicts are seldom confined to their point of origin and may spill over to other territories or nations. We have seen such spillover scenarios play out throughout history in sub-Saharan Africa and recently in Syria and Iraq. Third, because support for an insurgency frequently marginalizes local moderate factions, governance vacuums created by conflict are filled by radical groups. Any of the three outcomes will be devastating for Ukraine and European security more broadly.

For those nations directly affected by escalatory actions, there is clearly much more at stake. These are the voices not being heard on this side of the Atlantic. Indeed, the ongoing political and military standoff between Russia and the West is the most recent indicator that Europe’s security and economic architecture is experiencing a tectonic but not unwelcome shift. This shift emanates, on the one hand, from the long-standing desire expressed by major European capitals to be masters of their own house – economically, politically, and militarily. On the other hand, these same countries benefit from and want a predictable and stable environment in which Russia-EU relations will, by virtue of the fact they are economically interdependent, improve over time.

With a much greater interest in continental European peace and security, Berlin naturally prefers conflict management through dialogue with Russia. Washington’s goal, that the departure of Angela Merkel, who pursued de-escalation with Moscow, will bring hardliners to Berlin, remains elusive. In 2015 Merkel famously faced down Republican Senator John McCain who pushed hard to ship massive lethal aid to Ukraine. Her response, correct now as it was then, was that this conflict cannot be solved through military means.

Despite immense pressure from American media to isolate Germany on this issue Berlin’s commitment to de-escalation with Russia has been confirmed through the blocking of NATO arms shipments to Ukraine. Moreover, Chancellor Scholz refused a meeting with Joe Biden before the first of two Normandy Format meetings. Biden was determined to convince Berlin to agree to Washington’s agenda against Moscow despite the fact that Biden went out of his way to stop sanctions on the Nord Stream II pipeline and blocked Republican efforts to impose even more. It is clear that the American sanctions strategy has brought great harm to EU members by impacting 12 EU nations and 120 EU based companies. The EU declared these sanctions illegal and territorial overreach as they will very likely do again when Biden introduces his much tougher sanctions bill next week. To be clear, Biden’s initial reversal on sanctions was not intended to be a conciliatory gesture towards Russia but rather an attempt to ease the transatlantic divide over America’s policies on Ukraine.

Today, the Biden administration is vehement in their claim that a Russian attack on Ukraine is imminent and that increased tensions over Eastern Ukraine are a byproduct of a much deeper rift between Moscow and Western capitals. Even though European nations appear to be sidelined in Washington’s offensive, they have an opportunity to regain control over their own security.

Reviving the Normandy Format and the Trilateral Contact Group on Ukraine is important to de-escalating tensions with Russia. Russia, Ukraine, France and Germany have already met this week and will meet again at the beginning of February. These multilateral platforms may not directly address Moscow’s long-standing concerns regarding the enlargement of NATO, but they place EU countries like Germany and France as well as Ukraine and Russia, those with the most at stake in regional security, at the helm of conflict management. Moreover, these platforms produced robust treaties such as Minsk II and several rounds of de-escalation which indeed prevented war. A crucial first step in returning to the status quo ante is to initiate mediation between EU members and Russia. Angela Merkel was a critical player in this regard Chancellor Olaf Scholz has big shoes to fill. It is crucial that his government and their French counterparts re-establish a leadership role as soon as possible.

Meanwhile, both the US and the UK are preparing to pull some of their diplomatic staff from Kyiv with Canada likely to follow. These departures weaken the prospects for a diplomatic solution. More importantly, they send a disturbing signal to both European nations and the people of Ukraine. As one Kyiv politician noted: “On the one hand, [Washington tells Ukraine] how we should democratize. We stand with you. It’s your right to determine to join the West. We will stand with you against Russian aggression…Then Russia turns up the temperature and they’re the first to leave.”

In sum, our foregoing discussion highlights that the policy of a few nations are contributing to dangerous conflict escalation in a region where they do not have an immediate security stake. Looking ahead, the shaping of the European security architecture should be left to the EU, Ukraine, and Russia, which have the most to lose from any confrontation.

Table 1

| Escalation Scenarios | Scenario 1: Escalation Through Arming of Ukraine | Scenario 2: Ukraine’s President Zelensky Imposes Martial Law | Scenario 3: Targeted Operations by Special Forces in LNR and DNR | Scenario 4: Full-scale invasion of Ukraine by Russian Forces |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Likelihood | Most | ⟶ | ⟶ | Least |

| Anticipated Outcome | – Targeted military strikes and/or sabotage by Russia on targets in Ukraine, including ammunition depots and radar installations. | – Limited intervention by Russia; support for local ‘compatriots’ and anti-Kyiv leaders. | – If alongside UK and US forces, Russia intervenes with special forces. – If Ukraine acts unilaterally, Russia supports LNR and DNR fighters. | – Russia establishes the strategic ‘land bridge’ to Crimea. – Taking part of the ‘Novorossiya’ territory up to the Dnieper. |

| Escalatory Path | – The arming and training of Ukraine creates a ‘window of opportunity to strike targets in Ukraine at a low cost. – Russia strikes before Ukraine becomes stronger. – The greater the rate of arming Ukraine, the more imminent is a potential strike by Russia. | – Precedent exists: martial law was previously imposed on Russia-adjacent Oblasts in Ukraine to control the local political landscape ahead of the Presidential election. – The goal of another martial law may be to prevent perceived ‘shaping operations’ by Russia ahead of any use of force during crisis escalation phase. – The anticipated outcome is aggravation of the local population and intervention by Russia in support of ‘kin.’ | – Russia perceives any movement of opponent forces closer to its borders as an act of military hostility. – If the U.S and/or others’ special forces assist Ukraine, Moscow perceives this as movement of NATO closer to its borders; anticipated limited military intervention from Russia. | – Russia may decide to pursue the creation of a land bridge to Crimea; Mariupol is key if the Russians desire a land bridge to Crimea. – Russia may pursue the integration of the LNR and DNR which also articulated a desire to join Russia; Odessa, Kharkiv destabilized. |

Figure 1

Adapted from Hromadske.

Figure 2

Adapted from Wikimedia.

David Carment is a Senior Fellow at the Institute for Peace & Diplomacy and a Professor of International Affairs at the Norman Paterson School of International Affairs. He is the editor of the Canadian Foreign Policy Journal and the series editor for Palgrave’s Canada and International Affairs. His research focuses on fragile states, diasporas and foreign policy, and grey zone conflict. His most recent books include Exiting the Fragility Trap and Political Turmoil in a Tumultuous World. His research website can be found here.

Dani Belo is a teacher and scholar of international relations specializing in conflict management and security. He is currently an Assistant Professor of International Relations at Webster University in St. Louis, MO, USA. His research focuses on gray-zone conflicts, management of ethnic conflicts, NATO–Russia relations, and the post-Soviet region. Among other places, his work was featured at the U.S Army Judge Advocate General’s Legal Center and School, the Royal Military College of Canada, the University of Pennsylvania Law School Center for Ethics and the Rule of Law, and the European Commission.