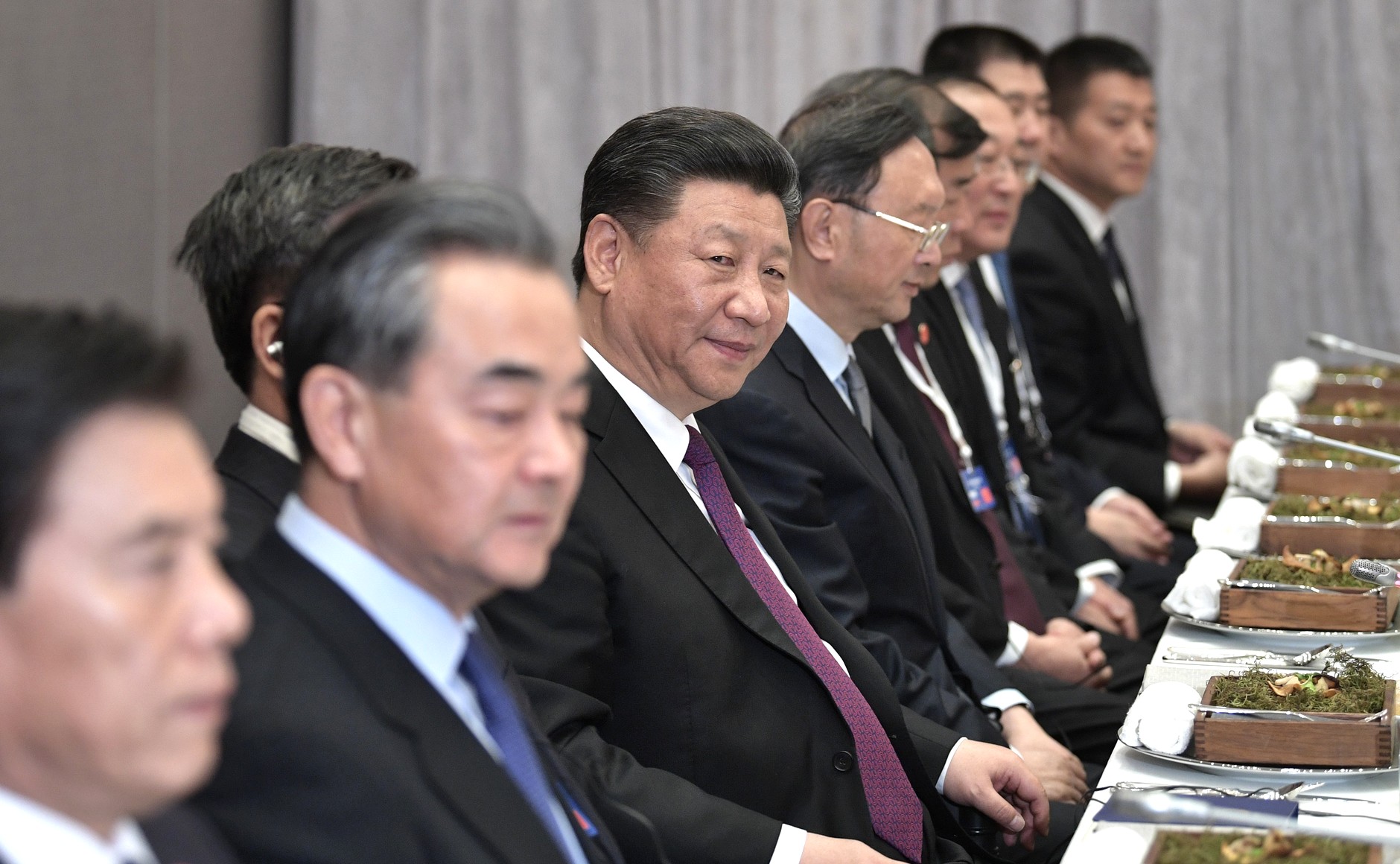

Photo from: Kremlin.ru, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

This paper is published as part of IPD’s China Strategy Project.

Liberals of all stripes, and Canadians in general, are uncomfortable with the rise of China. Xi Jinping as leader of the governing Communist Party of China rejects the universality of liberal values on principle and exercises brutal repression to preserve the Party’s political monopoly. His quest for the Great Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation ignores the aspirations of the people of Taiwan for their own vibrant democracy and erases the distinctive identities of Tibetans and Uyghurs alongside the linguistic and cultural practices of other minorities under Chinese rule. He has enshrined himself over the past decade as the sole interpreter of an ideology that combines Marxism-Leninism with the Chinese cultural tradition as he defines it. Alarmed at the repressive policies Xi implements at home and concerned about the elastic boundaries of the national destiny he propagates, Canadians witnessing the growth of China’s economic and military power are uneasy with the world taking shape. Recent polls say a clear majority want to reduce our trade dependence and even more believe that we can do so without suffering negative consequences on our prosperity and wellbeing.

As China outpaces regional and global competitors, other participants in the liberal order that emerged in the wake of the last World War are concerned for its future. That China challenges aspects of that order is beyond dispute. The extent of that challenge – and the scope of China’s dissent – are crucial for any rational and effective response that does not destabilize peace or threaten the planet. Those ensconced in the firm belief that liberal values form the essence of humanity and convinced that these were baked into an order led and maintained by the United States of America experience the rise of China as an existential threat. But not all experience China that way. Over-identification with a liberal model rooted in Euro-American history and experience clouds rational discussion and obscures a realistic and accurate understanding of the nature of China’s challenge.

The Asian Perspective

In a self-regarding perspective that reaches only to the dawn of modernity and Western dominance over the past few centuries, liberals of the West misconstrue the import of China’s ‘national rejuvenation’ and analogize it to the rise of Germany in the half-century before the Great War. Asians understand the way China understands itself. The identity of China is as a civilizational great power. It is a great power consciousness that Xi Jinping emphasizes in practically every speech, including his greetings to the citizens of his country on New Year’s Eve.

For practically all Chinese, the idea of China is equated with being a great power in the world. Furthermore, a great number see their own personal identities bound up with the project of China’s state power. This is not new, nor does it derive from Marxism-Leninism. It is inextricably bound up with China’s Confucian tradition where the aspiration was to ‘assist Heaven’ to bring order and manage the ‘All Under Heaven’, Tianxia, with the ultimate aspiration of educated commoners to act as ‘tutors to the King’ in the management of state affairs according to the Will of Heaven: Tianming, otherwise referred to as the ‘Mandate of Heaven’.

China’s Asian neighbours were acutely aware of Chinese sensitivities and pretensions and participated in its hierarchic order to various degrees. Island Japan stood apart, but it did not dispute the centrality of Chinese civilization. China’s Asian neighbours proffered the appropriate deference to coexist with China, and in return China offered benign indifference to their internal affairs. As long as it was not challenged in its self-regard, China did not care. So, with long memories at their disposal and with very recent experience of the hypocrisy of Western universalism in the form of colonialism, Asians know how to live with China’s rise, and on New Year’s day brought into effect the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) which brings together ASEAN and China along with both Japan and South Korea, with Australia and New Zealand also in the mix.

As the President of the Institute for Economic Cooperation of the Chinese Ministry of Commerce put it, “RCEP is the 19th FTA China has signed, it is the FTA of the greatest global scope and will play an important role in the expansion and increasing standard of China’s opening to the outside.” Furthermore, he added: “China has under the umbrella of RCEP established free trade with both Japan and the ROK, which has not only built a basis for a three-sided high-quality FTA with Japan and the ROK. It has also positively assisted in the promotion of accession to a higher standard FTA with transpacific partners” (hinting at accession to the CPTPP, author’s emphasis). The article appears to make clear China’s touted commitment to a rules-based multilateral trading order in which regional free trade zones play a promotional and supportive role.

It is absolutely clear that China’s Asian neighbours, including Japan, do not see the rise of China and the decline of rules-based order in zero-sum terms. To pretend otherwise is nothing less than Eurocentric Western hubris.

Ambiguity in China’s Exceptional Challenge

No one is suggesting, least of all this author, that we should acquiesce to every aspect of Chinese domestic and foreign behaviour and treat all its pretensions with deference. We do, however, need to recognize the following:

- China is fully committed to a global order with the United Nations and its associated institutions at its centre. China is the largest contributor of peacekeeping forces among the permanent five of the UN Security Council and the second-largest contributor to the UN’s peacekeeping fund;

- On the 20th anniversary of its accession to the World Trade Organization, China has reaffirmed its commitment to the multilateral trading order and has demonstrated greater adherence to its trading rules and willingness to abide by its arbitration than has the United States;

- China has never invaded and occupied territory without UN sanction (unlike the US) and generally abides by its treaty commitments. Nor does it place domestic law above international law (unlike the US).

This recognition does not exclude acknowledgement that the rule of law in China falls well short of the standards of constitutional liberal regimes, in particular in the area of individual rights. Furthermore, the deficiencies of the rule of law in China make it less likely that any individual or legal person, domestic or foreign, can get a hearing before an independent court in any politically sensitive case where the communist regime is implicitly a party. Canadians saw this in the case of Michael Kovrig. This does not mean, however, that Chinese justice is arbitrary in all cases. Canadians may be surprised to learn that foreign corporate litigants are successful in the majority of their cases before Chinese courts, especially in the highly publicized area of intellectual property.

China poses exceptional challenges, but its status as an exception has clear limits. It remains broadly supportive of the current world order. China has found a coterie of clients and hangers-on, but there is little to suggest any likelihood of a hegemonic bloc, nor is there any real evidence of Chinese ambition to construct a coherent economic network for which it takes political responsibility.

Reassessing Chinese Behaviour

Recently there have been efforts to equate Chinese and Russian attitudes towards their ‘near abroad’ with reckless charges of ‘irredentism’. China has settled its territorial disputes with nearly all of its territorial neighbours. India and Bhutan are the only countries with which China disputes its land border. Critics naturally raise the issue of the South China Sea and Taiwan as well as the Senkaku/Diaoyutai dispute with Japan. In each of the cases of China’s maritime borders, and the issue of China’s sovereignty over Taiwan, China has not shied away from militarized threats.

Nonetheless, even though China rejected the jurisdiction of the UN Court of Arbitration on the South China Sea, China maintains that it continues to support the UN Convention of the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) which the US has so far declined to ratify. Beijing is also involved in active negotiations with ASEAN on a Code of Conduct for the South China Sea. The details of the Senkaku dispute are too detailed to rehash here, but it is sufficient to say that not all the legal weight is on the Japanese side. The weight of international opinion is that Taiwan is not a sovereign state. The issue there is whether the People’s Republic of China can claim it and whether it is entitled to enforce its claim by military means. Here again, the weight of international opinion, broadly shared by Canada, is that the PRC is not entitled to enforce its claim against the will of Taiwan’s population, which consistently demonstrated its determination to uphold its democratic autonomy.

The case of Hong Kong is also complex – it was administered as a British Crown Colony where more than 2/3 of the territory was a 99-year lease scheduled to revert to Chinese sovereignty in 1997. While China’s central government may have betrayed hopes that Hong Kongers will be able to elect their own chief executive under universal suffrage, China made no such explicit commitment under the Joint Declaration that governs the reversion of Hong Kong to Chinese sovereignty, nor did the British authorities in the 150 years in which they governed Hong Kong ever institute an executive fully accountable to the local population.

The National Security Law of Hong Kong that the PRC National People’s Congress promulgated in 2020 does violate provisions of the Joint Declaration with respect to the UN Convention of Civil and Political Rights, but there is no real enforcement mechanism beyond that provided by the UN Human Rights Council. The ‘one country, two systems’ premise has been hollowed out, but this was never anything more than a promise, with no legal or constitutional backing and certainly no enforcement mechanism under international law.

We have the right to complain, and complain we should, on behalf of the people of Hong Kong. But we also should acknowledge that the provocative disturbances between 2014 and 2020 targeting police and state institutions set the stage for a heavy-handed crackdown. That crackdown was by Hong Kong’s own institutions with a pedigree to its colonial past and not by any direct intervention by forces deployed by the Mainland. On the whole, the failure of the one country, two systems model was an institutional failure in which Hong Kong’s establishment, the British who negotiated the handover and the CCP in Beijing all share blame.

In short, therefore, it is a distortion to look at PRC relations with Hong Kong, Taiwan and the South China Sea as evidence of expansionism or hegemonic intent. China has long made its intentions towards these clear and consistent. There is no evidence of a growing appetite for outward conquest.

What of the Belt and Road Initiative? A closer look at the initiative and its implementation demonstrates no malign intentions and questionable payoff on Chinese ambition. Since the initial announcement of the BRI in 2013, the project has grown to encompass Latin America as well as East Africa and virtually the entire supercontinent of Eurasia. Nonetheless, the pace of investment has slowed significantly over the past several years as multiple difficulties have surrounded them. Even the earliest showcase project in China’s ‘all weather friend’ – the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) – has been downsized, with both investment viability and serious security concerns considerably diminishing the prospects of its deepwater outlet on the Arabian Sea, Gwadar. Pakistan and Sri Lanka (another close partner) are struggling under the contracted debts. This does not mean that the entire initiative was designed with ‘debt traps’ in mind. It simply means that the ambition of the initiative failed to match economic realities and the Chinese promise of aid ‘without conditions’ produced white elephants for greedy politicians that had no way of paying for themselves.

This does not mean the entire initiative was ill-conceived, nor that it failed to have positive developmental spin-offs. There is little doubt that Chinese efforts have turned around the investment climate in Africa and stimulated badly needed infrastructure investment. Furthermore, on balance it has yielded considerable goodwill in Asia, Africa and the Caribbean as well as in Central Asia. But fears of growing Chinese hegemony in Central Asia, East Africa and Eastern Europe now ring strangely hollow. Ethiopia, once a Chinese investment success story, is now in the grips of a bloody civil war. Sudan is plunged in deep political uncertainty. South Sudan still struggles to maintain coherence as a state on anything but paper. And the Middle East is, if anything, less coherent politically than it has been at any time since the end of the First World War. There is virtually no evidence that the BRI has succeeded in replicating the ‘Chinese model’ or the ‘Chinese solution’ anywhere.

Chinese support may shore up some ‘bad actors’, but only where those actors are in firm control of domestic institutions. In other cases, China keeps a wary distance even from ‘enemies of their adversaries’ such as the Taliban in Afghanistan. Almost a half year after the Taliban took Kabul, China is in no hurry to recognize the Taliban Emirate. Rather than consolidate the alignment with Pakistan, cracks have opened in China’s relations with the Pakistani military, even in the midst of the worst tensions between China and Pakistan’s arch-enemy India in more than a generation.

The reality demonstrates that China is neither the unstoppable juggernaut that some people fear, nor does it harbour an unquenchable quest to undermine and destroy our way of life. Instead, it is a fearful regime that yearns for space to survive in a world where its own norms are criticized as are the genuine improvements it has brought about for its own people. China is neither as beneficent as it claims nor as malevolent as it is maligned.

The Chinese Communist Party exercises a firm grip over the territory and population under its jurisdiction, but its influence diminishes dramatically the further one gets from its frontier. There, its influence is limited to the blandishments it proffers and the limited sanctions it can wield. It has few friends on principle, but only a fellow feeling among those other regimes beleaguered by populations they cannot trust. A league of authoritarians led by China and Russia may amount to little more than a passel of paranoiacs, anxiously peering in the rear-view mirror. Russian interference in the US election and the Brexit referendum was disturbing – but the motley characters dredged up by investigations were hardly capable of promoting a coup in a country club let alone overturn a vibrant democracy.

Can the West Influence China? And How?

It is a truism to look at the relationship of China with major Western countries and speak of ‘the end of engagement’. The degree to which the ‘post-engagement’ period is cast as a ‘new Cold War’ is in debate. But no one disputes that the era of engagement is over. Furthermore, the ‘flaw’ of engagement is generally recognized as one where we interacted with China according to our rules and we expected that China would then accept those rules and become socialized into Western norms. Despite consistent evidence the Chinese Communist Party has rejected Western norms, it was only once Xi Jinping explicitly repudiated universal values and began to tout China’s own normative beliefs that this perspective was put to bed. At the same time, a shifting balance of material power, both economic and – at least in terms of hardware and organization – military power, demonstrated that China was ready to deploy that power in defence of its dissent from the West. Donald Trump accelerated this process through a more confrontational stance and explicit recognition that China was America’s rival.

On the Chinese side, we can date a shift from conditional engagement to self-regarding assertiveness – first with the revision of the one country, two systems formula in Hong Kong, then the explicit subordination of Special Administrative Zone’s institutions to the national security norms prevailing in the PRC. In a parallel fashion, Beijing’s approach to Taiwan is increasingly characterized by military pressure and away from political blandishment. A policy of blunt assertiveness where possession is nine-tenths of the law in the South China Sea speaks for itself. The violent standoff along the Sino-Indian frontier is another data point, alongside the harsh repression in Xinjiang with no pretence of even face-saving nods to Western sensibilities. The message is clear: 中国办自己之事 – “China will take care of its own affairs.” The unspoken corollary is that Western objections play no role in Beijing’s policy calculus.

Covid, and a growing rift with the West led by the US, act to insulate China from Western influence. As human contact declines, as trade, technology and scientific relations come undone the positive incentives for a shared outlook fall away, with blunt force the sole remaining channel of influence. It isn’t that deterrence is a more effective tool to influence authoritarian regimes like China’s. Rather, it remains the means available once alternatives have been discarded.

In issues like the survival of Taiwan’s democratic government, deterrence is indispensable. Where force is already being deployed, the availability and willingness to deploy counterforce is the only reasonable response. But deterrence does not foreclose diplomatic solutions. It simply telegraphs that force will be met by force. Therefore, each side must explore alternatives short of war to achieve their most important goals. The West’s goal with respect to Taiwan is to safeguard the hard-earned right of Taiwanese people to form a democratically accountable government and to ensure that military force does not become the language of diplomacy in East Asia. The West insists Beijing must pursue the goal of reunification peacefully, consistent with the support of the people of Taiwan. In effect, Taiwan is one test of China’s peaceful intentions.

By all means, China’s claims in the South China Sea must be challenged practically, but the normative challenge should be pursued in coordination with China’s ASEAN neighbours with concerted demands that China conform to UNCLOS, a treaty it has signed and ratified. This requires that the US ratify that treaty also.

There is little the West can do to counter China’s brutal practices in Xinjiang. The failure of the Islamic world to come to the support of their Muslim brethren deprives would-be supporters of Uyghur human rights of the most potent diplomatic tool. Banning imports produced with forced labour is important symbolically and may loosen dependence on China-anchored supply chains. However, the latter is a double-edged sword. Lessening dependence on China-anchored supply chains reduces vulnerability to Chinese sanctions, but also eliminates bandwidth in mutual influence.

There are three problems with the strategy of ‘decoupling’. First, it may not be practical at a price we can afford. Second, it reduces channels of mutual influence that encourage both sides to reach a mutual accommodation. Third, impeding and reducing the two-way (and multi-vector) flow of factors of production significantly increases costs and reduces welfare for both parties. As we have already seen with Trump’s tariffs, the party imposing the cost pays the higher price. The loss of positive incentives for cooperation may do more harm than the supposed benefits of reducing trade dependency would justify. Furthermore, the quicker the pace of decoupling, the more it reduces the marginal impact of the threat of further sanctions.

It is obvious that Xi Jinping’s insatiable quest for global status means that the greatest impact on China may be through conditional cooperation inside the institutions and fora of global governance coupled with united and unequivocal criticism. Xi Jinping craves the echo of applause from abroad. Global prestige cannot be achieved domestically, nor can it be manufactured through censorship. To be sure, censorship may snip out criticism, and applause tracks can be manufactured for domestic consumption, but a global China is unable to seal itself off from the world. In fact, the best thing the West can do in the competition with China is to maintain its own prestige globally. ‘Soft power’ is not easily deployed, but more importantly, its accumulation is broadly proportional to the beneficence of material power. Spread the wealth and demonstrate your availability, only then will you achieve soft power credibly. China makes great efforts to spread the wealth but has been much less successful at demonstrating its availability. China is quick to offer and quick to withhold. It leaves the impression everywhere that its generosity is self-serving.

Addressing China’s Challenge

While some Western observers and misguided Canadian analysts cast envious glances at ‘the Quad’ as a prototypical ‘like-minded’ coalition, the reality of its members’ foreign policy suggests otherwise. India maintains normal multilateral meetings with China and Russia and Sino-Indian trade reached new heights this past year. Even discounting India’s lapses from democratic values, its alignment with the West appears more like a hedge than a wedge directed at Chinese ambitions.

Much Canadian hand wringing about the existential threat of China to the West is based more on irrational fear and envy than sober reality. Yes, China challenges liberal values and norms – especially in the realm of individual human rights and democratic pluralism. At the same time, China shares with Canadians a belief that the deep purpose of modern governance is to promote collective prosperity and wellbeing reflected in the improvement of individual lives. China has proven this on a vast scale and has the ambition of demonstrating this to the developing world. That is a competitive challenge, to be sure – but it is a virtuous and benign one with positive-sum outcomes.

This is a competition the West should willingly embrace and refrain from turning into a zero-sum confrontation. We should take up the challenge and give the Chinese model the chance to fail on its own terms, while at the same time ramping up the attractiveness of what the West has on offer. In the rush to securitize our relationship with China, Canada is in retreat from the global stage and huddling in fear within the narrow core of NATO. Africa, Asia and Latin America have no interest in our liberal nostalgia for the Cold War.

US President Biden is well aware that the key to outcompeting China is to prove that the liberal democratic path yields better outcomes and greater prosperity. So far, he has been hard-pressed to demonstrate it. Let us compete with China on results-based governance that generates popular support. The West needs to show that an individual, rights-based model of governance is capable of generating collective action in the interest of all – in the economy, in public health and in the natural environment. Without that, our rhetoric on rights’ will remain just that.

US President Joe Biden recently summoned a summit of democracies – but to what end? If the purpose of the gathering was to shore up the rules-based order and ensure the future of liberal global governance, then the premise should be to support the global governance institutions associated with the United Nations, to coordinate among democracies to press for the highest-common-denominator solutions to global problems and to promote further human rights. What is needed is a collective lobby group to work within existing institutions, not an alternative that sharpens the global divide and apes the dysfunction that currently afflicts the US body politic.

By all means, let us compete with China, and confront it where necessary. But let us be clear-eyed about our purpose: it is not to ‘defeat’ China but to advance the cause of the planet and humanity. Going to war with China will solve none of our problems. Today’s PLA is not that of the Korean War. It can credibly challenge the US and there is no reassurance that a war with China will be limited in time or space. At the same time, no solution to the global challenge of climate change is possible without Chinese cooperation. Lose China, lose the planet.

Jeremy Paltiel is a Professor in the Department of Political Science at Carleton University and a Senior Fellow at the Institute for Peace & Diplomacy.