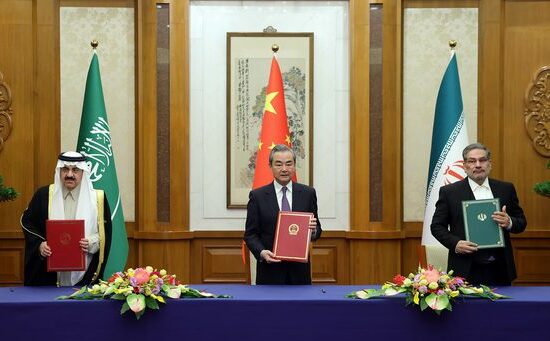

Rafael Mariano Grossi, IAEA Director-General, met with Dr. Ali Bagheri Kani, Vice-Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Islamic Republic of Iran, during his official visit at the Agency headquarters in Vienna, Austria. 2 December 2021. The Director-General is joined by two of his senior staff Mark Bassett, Special Assistant to the DG for Nuclear Safety and Security and Safeguards and Diego Candano Laris, Senior Advisor to the Director General.| Image credit: Dean Calma/IAEA

By Ali Ahmadi

After months of stalled negotiations aimed at reviving the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), more commonly referred to as the Iran nuclear deal, the Raisi administration agreed to resume the talks with world powers in Vienna. The first week of talks ended with a diplomatic stalemate, sending Western delegations to their capitals for further consultations. While the talks resumed last week, JCPOA signatory members, without the United States, continued the negotiations in a more combative environment. The elevation of the new conservative President Ebrahim Raisi and the delay in Iran’s return to negotiations had already led to a wave of pessimism from Western policy-makers and punditocracy.

The dominant narrative has been centered around a “ticking clock” to salvage the deal. In fact, it has now become fashionable to be pessimistic about the prospects of the renewed nuclear talks. Yet, one must remember that the original JCPOA negotiations evoked deep and widespread fatalism at various points over its grueling two-year span. There was finally a breakthrough, at least in part, because of the propulsion provided by the political necessity that they succeed for national security reasons. The sides, simply put, lacked better options and faced a volatile future if they relented. The same situation exists here again. To quote Margaret Thatcher, there is no alternative.

Iran’s Economy in the Shadow of Sanctions

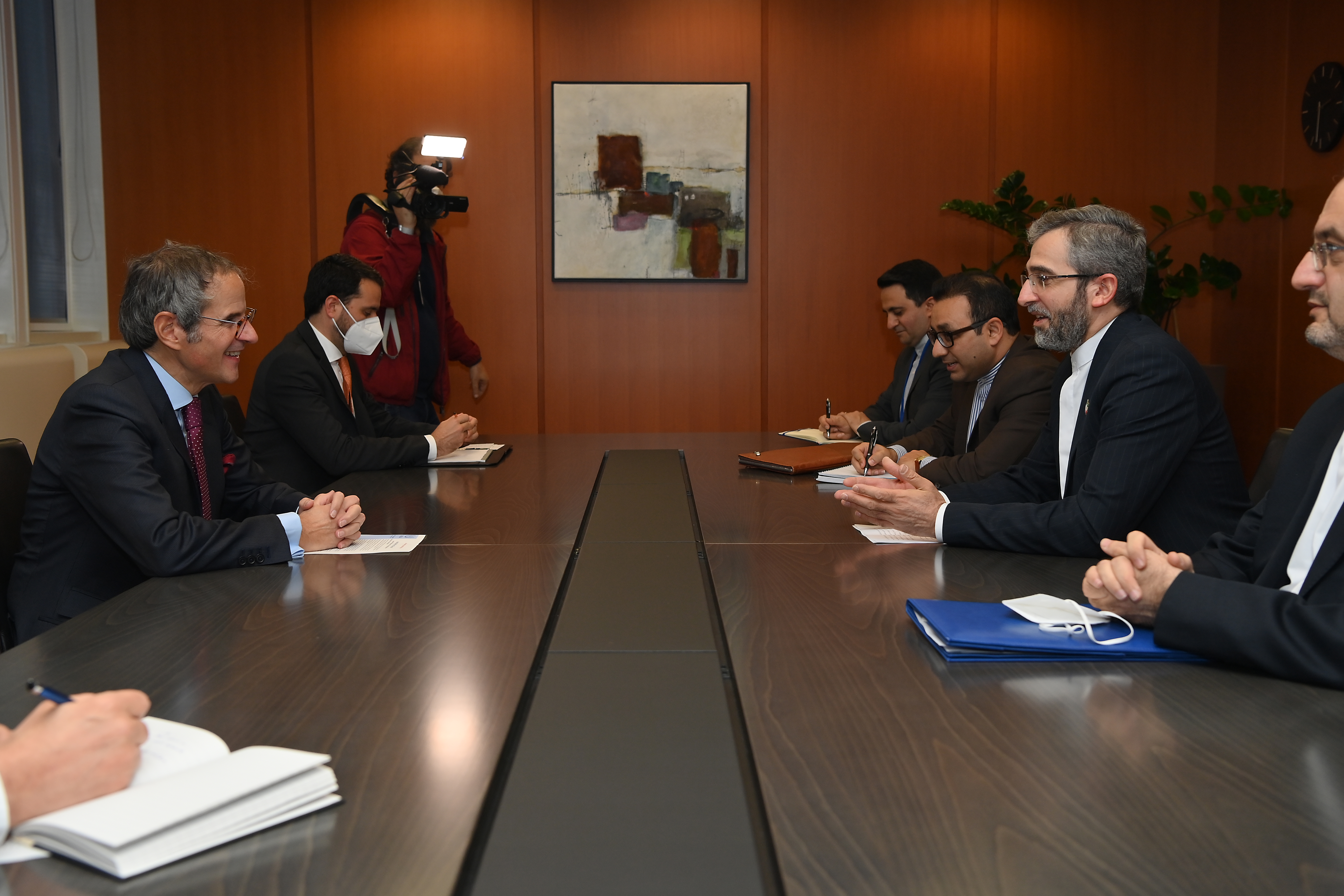

With the defeat of Trump’s “maximum pressure campaign”, the Islamic Republic proved that it was neither on the verge of collapse nor desperate for any brief economic respite – a reality that Iranian negotiators seem keen to clarify during this round of talks. However, the Iranian leadership is also well-aware of the fact that the economy cannot sustainably develop with US sanctions in place, preventing long-term foreign investment and fruitful trade partnerships with most countries. In this vein, the Raisi government has mainly focused upon the Asianization of Iranian economic and diplomatic ties to defuse the long-standing issue of sanctions. As Raisi accelerates Iran’s economic interactions with China, he is also engaged in ongoing efforts to improve ties with regional countries, including Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates. Amid the United States withdrawal from its regional commitments and renewed diplomatic efforts to revive the JCPOA, the two regional powers have shown more flexibility in their dealings with Iran. Nonetheless, these new initiatives could be undermined if Iran fails to reach some truce with the West on the nuclear front.

Much has been made of the Sino-Iranian economic relationship in light of the 25-year strategic partnership signed between Tehran and Beijing earlier this year. But, as it stands today, this relationship is fairly one-dimensional with Iran exporting petroleum, for the most part, to China in exchange for inputs. The Chinese private sector and even many of its state-sponsored enterprises are not immune to US sanctions. The inability of Chinese financial institutions to invest in Belt and Road Initiative projects inside Iran is a key reason as to why the country currently has little involvement in this trans-continental mega project. It is important to underline that the 25-year agreement with China was also never supposed to be an alternative to the JCPOA nor a viable strategy to nullify sanctions. Instead, it was meant to be an add-on to it, given that it is unlikely to be implemented without certain steps including the reconstitution of JCPOA-related sanctions relief, according to former Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif.

Furthermore, the process of improving ties with Persian Gulf countries will certainly be complicated by the continuation of the status quo. After all, the countries in question are US military partners and the last few years of US-Iran tensions have involved a parallel kinetic track of escalation in the region. These tensions seem to have leveled over the last year due to the prospect of reviving the agreement. If these regional tensions were to restart, they could threaten the new more positive dynamic between Iran and its neighbors in the Persian Gulf region.

An imperfect reconstitution of the Iran deal would still improve Iran’s current economic conditions and strengthen the country’s capacity to manage future uncertainties—provided that it results in real economic opportunities. There is a set of long discussed policies such as monetary and subsidy reforms that could greatly improve both the productivity and resilience of the Iranian economy. Yet, these reforms are nearly impossible to implement with US sanctions in place. Thus, it is completely understandable for Iran to insist on some form of guarantee for sanctions relief, providing a meaningful level of economic benefits for the country. In order to revive the deal, however, Tehran should be flexible on the outstanding technical issues pertaining to its nuclear compliance.

No Realistic Plan B

The Americans, on the other hand, need to acknowledge the myriad of reasons, articulated by many currently in the administration, that the maximum pressure campaign was a disaster for US national interests. Even the policy’s most fawning cheerleaders are now left to defend it as a failure but “not necessarily an open-and-shut case of foreign policy malpractice.” Therefore, there is no remotely compelling reason to return to Trump’s maximum pressure campaign and rebrand it with another name like the “Plan B” and expect for it to yield different results.

The Trump administration has already fired every bullet in the sanctions chamber. Unlike the Obama administration’s gradualist approach, Trump’s strategy, molded by Pompeo and Bolton, favored piling on as many sanctions as possible to create a shock effect and crush the Iranian economy. But, it overplayed its hands with sanctions to the level that it almost lost its effectiveness in bringing about a desired change of behavior. Robert O’Brien, Trump’s National Security Advisor later explained that “one of the problems we have with both Iran and Russia is that we have so many sanctions on those countries right now that there’s very little left for us to do.”

Many hawks in Democratic circles seem to believe that Biden reclaiming the support of European allies would mean more pressure is now possible. The real problem is that Europe, unlike two decades ago, is no longer a powerful force capable of inflicting heavy costs on Iran for non-obedience. The continuation of US secondary sanctions perished Iran-EU economic relationship over the years, pushing Iran to rely more on China and Russia for trade and investments. In fact, US officials have been rather transparent about the fact that their only remaining option to exert real pressure on Iran is to seek cooperation from the Chinese.

During the Obama administration, Beijing was more cooperative and inclined to bandwagon with Washington on the Iran nuclear issue. Today, China understands that there has been a structural shift in US policy and that something resembling a Cold War is on the horizon. This put the notion of seeding to Washington’s ambitions in Asia in a very different political context, especially as it would free up more American resources to be shifted and invested towards the Eastern side of the continent.

Both Obama’s ‘‘Pivot to Asia’’ policy and Trump’s early plans for a shift to “near-peer competition” were largely derailed by their focus on the Middle East – and especially Iran. A senior Obama administration national security official once acknowledged that even after the administration had made the decision to focus on China, “about eighty percent of our main meetings at the National Security Council have focused on the Middle East.”

Lastly, the United States has, over the last two decades, justified its Iran policy on the need to tackle regional instability. While several countries in the region initially opposed the JCPOA, Saudi Arabia and other Persian Gulf countries now support its revival. A new round of regional escalation is likely to sink the tenuous new detente between Tehran and Riyadh, which is the greatest hope for long-term stability across the Middle East. This indicates that the success of the Vienna dialogue is not only vital for Tehran and Washington, but also critical for regional peace and stability in the post-US withdrawal era.

In recent days, there have been early indications that all sides are already proceeding in a more productive manner. In particular, it seems like Tehran and Washington are trying to look past each other to other opportunities and priorities. Regardless, without reaching some limited modus vivendi, a breakthrough is simply not feasible. With no other viable alternatives, all the negotiating teams and the governing elites in their respective capitals must also consider unattractive policy avenues to save the hobbled nuclear agreement and avoid prolonging this international crisis.

Ali Ahmadi is a researcher of geoeconomics and geopolitics focusing on U.S. foreign policy towards the Middle East and sanctions. His work has been published by The Diplomat, The National Interest, Palladium Magazine, and others. Follow him on Twitter or LinkedIn.