On March 24th, the Institute for Peace & Diplomacy (IPD) hosted a panel discussion on ‘Vaccine Diplomacy in the Middle East.’ Since the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, Middle Eastern countries have rushed to gain access to foreign vaccines. In this competitive environment, China, Russia, and the United States have all offered to export their vaccines to regional stakeholders in the hope of outmanoeuvring the other in winning hearts and minds in the region. With US regional allies including some Persian Gulf states, Turkey and Egypt importing vaccines from Beijing and Moscow, American vaccine diplomacy and soft power appears to be overshadowed in the region. The strong emphasis on vaccine diplomacy very much reflects the ongoing great power competition where world powers make their best effort to use vaccines to deepen trust and their influence in the post-COVID-19 regional order.

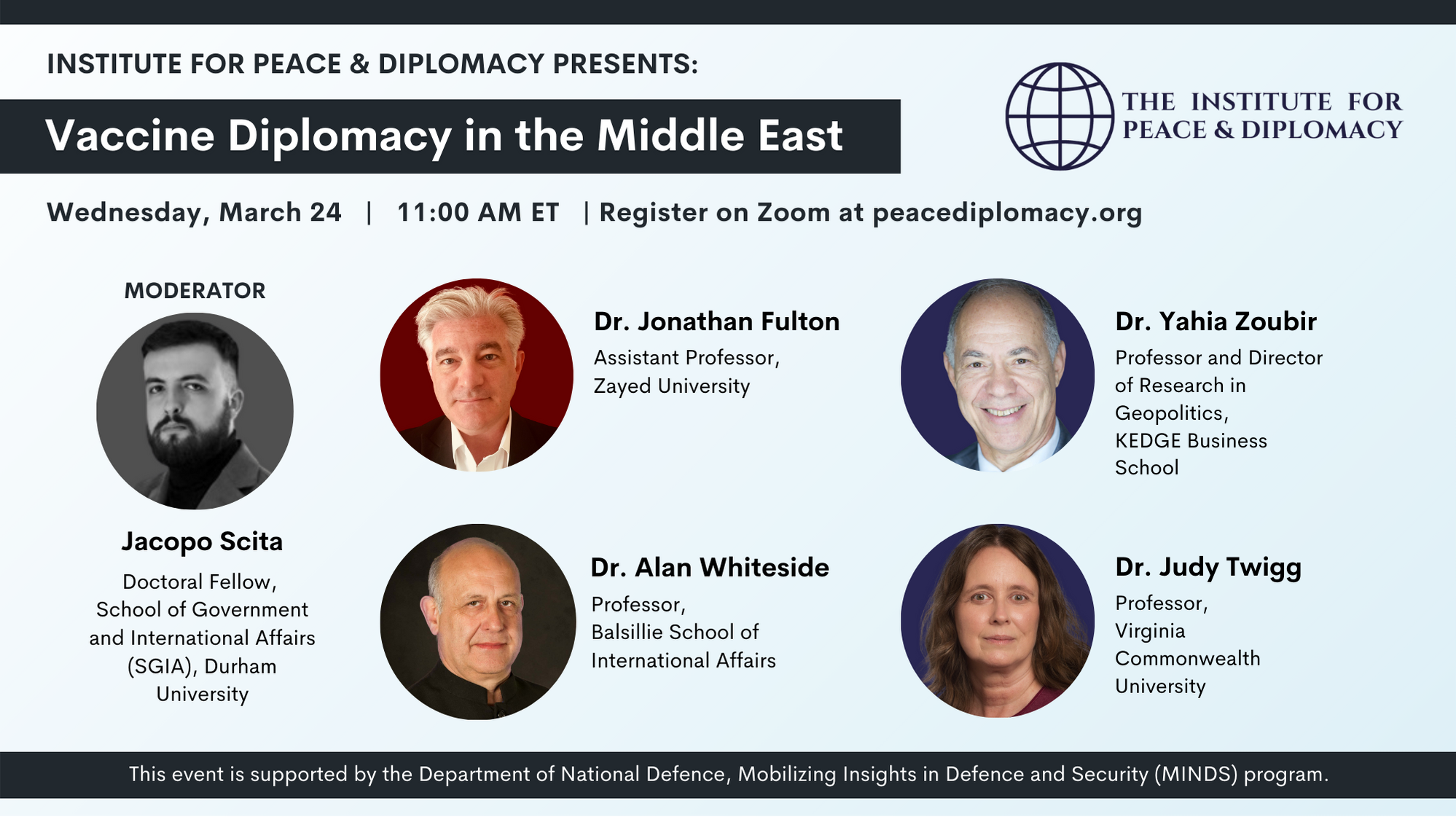

Our four distinguished panelists included:

- Dr. Jonathan Fulton, Assistant Professor of Political Science at Zayed University and Nonresident Senior Fellow for Middle East Programs at the Atlantic Council

- Dr. Alan Whiteside, Advisor at the Institute for Peace & Diplomacy, and Professor at Wilfrid Laurier University’s School of International Policy and Governance and at the Balsillie School of International Affairs

- Dr. Yahia Zoubir, Professor and Director of Research in Geopolitics at KEDGE Business School

- Dr. Judy Twigg, Professor of Political Science at Virginia Commonwealth University

This panel was moderated by Jacopo Scita, Doctoral Research Student in the School of Government and International Affairs at Durham University.

Introductory Remarks

Dr. Jonathan Fulton: I’m not a public health expert by any stretch. I’m a political scientist and I live in Abu Dhabi where I’ve been since 2006. I’ve been watching China-Middle East relations in general and specifically China and the Gulf. Now it’s been very interesting because I started my PhD in 2011 looking at China’s relations with the Gulf monarchies and I remember talking to somebody at that point in a research interview and he said ‘How are you ever going to stretch this into a hundred thousand words? China and the Middle East there’s nothing there.’ By the time I was finished, that changed quite a bit.

I’m working on a book right now that I hope to submit next week and it’s led me to read a lot of the earlier literature on China. Middle East relations from the past 20 years and even 10 years ago what you would find is that everybody described it as China buying a lot of energy and sells a lot of cheap stuff and that’s pretty much the extent. Now, what you can see, especially since the Belt and Road was announced in 2013, China’s gone from simply an energy consumer and an economic partner to really having a much greater set of interests in the region. It’s a political actor, it’s minimally a security actor and what we’ve seen in the past year is increasingly a governance actor as well, which is a very unusual situation because typically for issues of development or policy, countries in the Gulf would look towards the West. They have a lot of history with the UK and of course with the US as well. What we’ve seen for the past year,

and I don’t mean to insult our friends and neighbors in the UK or the US, but those countries have not really handled this in a very capable manner.

China, on the other hand, where it started around this time last year, as being perceived as kind of the victim that was the recipient of a lot of aid from the region, really got a handle on it quite quickly. We could debate the means, it was quite draconian and the people in Wuhan I’m sure were not very happy with the way it turned out but in terms of issues of governance countries here in the Gulf would look at how China’s handled this and they find it really quite appealing and that’s not just an issue of pandemic. This also extends into other issues as well. We tend to think of Western democracies as having a lot of the answers for development and policy issues. What we see in the Gulf is these are not democracies by any stretch. When they look at China, they see a country that has really handled a lot of developmental questions in a way that’s very attractive. If you can go from one of the poorest countries in the world in 1978 to the second biggest economy without any kind of political reform but massive economic growth – that’s tremendously attractive to a lot of authoritarian countries around the Middle East. When you look at how China’s kind of solved some of these development issues and how they’ve handled this pandemic, you’ll see that China’s presence in the Gulf is actually quite deep and broad.

Dr. Judy Twigg: I’ll focus specifically on vaccine diplomacy looking at Russia which is my area of expertise. In the global vaccine race, Russia was very clearly the first out of the gate in some ways. Russia’s Sputnik V vaccine (‘V’ is for victory) was the first COVID vaccine in the world to be approved by a national government back in August of 2020. Russia was aggressively marketing Sputnik V well before any of the Western vaccines had cleared regulatory approval. Sputnik V is now registered in 56 countries around the world. As of today, Vietnam has been added to the list and it’s hard to keep up because that number is going up pretty much every day. Many countries now have deals to receive Sputnik V doses straight from Russia. Even more are set to receive Sputnik V doses that are manufactured somewhere else like India or they’re set to receive the formula and the technology so that they can make Sputnik V themselves.

What are Russia’s goals here? There are three vaccine diplomacy goals at work in Russia. First is that Sputnik V is a symbol of Russia’s return to great power status. It’s about pride, respect and national stature. Being the first in the world to blaze the trail for the way out of this once-in-a-century global pandemic. It puts Russia back on the map as a scientific and technological power. Russia is trying to change the narrative here. Russia is no longer some drunken backwater that relies exclusively on the sale of oil and natural gas and minerals and other things that you can dig out of the ground. They portray Sputnik V this way quite deliberately. When the vaccine was first approved, it had a website and a prominent feature on that website was a button that you could push as the website loaded. There was a built-in delay and as you push this button, it told you to turn your audio all the way up and the sound that you heard over the audio was the ‘beep beep beep’ that you heard broadcast from space back in 1957 when the Soviet Sputnik satellite was the first man-made object to be sent into space. That was a hallmark moment for Soviet superiority in the space race and it’s not an accident that they’re evoking that memory now with the very name Sputnik for their vaccine.

A second goal that Russia clearly wants to achieve here is the exercise of soft power. Poor and middle income countries, including in the Middle East, are desperate for access to vaccines and Russia realizes that there’s potential diplomatic benefit from appearing as a savior during this unprecedented global crisis. In particular, Russia is taking great pains to contrast its own generosity against the relative selfishness, at least up until recently, of the US, UK and other European countries that gobbled up all of the first available doses of Pfizer, Moderna and the other Western vaccines through these pre-purchase agreements. The rich countries pre-purchased enough vaccine early on to cover their own population several times over, leaving the rest of the world with nothing. Russia is very anxious to highlight these inequities in its own role in solving those inequities.

Third and lastly, Russia sees Sputnik V as a business opportunity. COVID vaccines are a multi-billion dollar business and Russia obviously wants to maximize market share. They’re offering Sputnik V at about 20 dollars for a full course of two doses. That’s quite a bit cheaper than Pfizer or Moderna. There’s also a longer term set of interests here. Russia traditionally has not been much of a player on global pharmaceutical markets and they’d like this vaccine to be a wedge to get other countries to consider buying other drugs and pharma products from them as well.

In closing, there are several important caveats here when thinking about how likely it is that Russia is achieving these goals or will be able to achieve these goals. For now I’ll mention just one. The way Russia proceeded with Sputnik V didn’t exactly inspire confidence at first. Both international consumers and domestic consumers inside Russia have lingering doubts about Sputnik V because it was approved before it had even begun large-scale clinical trials. They put the cart way before the horse and there’s a correct perception that development of this vaccine was rushed. They skipped the line, so to speak. It didn’t go through full scientific and regulatory vetting because of top-down political pressure to be first to be the first in the world. There was a fear that this may have impacted the vaccine’s safety or its quality. Putin made a huge gamble when he launched this thing before it was proven. Since then, the vaccine’s safety and efficacy has been confirmed and results have been published in the lancet to an international peer-reviewed journal so it’s a gamble that’s paid off. The risk was tremendous including for potential partners in the Middle East which I’m sure we’ll talk about later on.

Dr. Yahia Zoubir: I don’t have a title of vaccine diplomacy simply because I would like to submit to you, for those who have done any research on China’s health assistance and health aid to the developing world. That was born basically a couple of years or so after the foundation of the People’s Republic of China. It goes way back to the 1950s and if you have looked at China’s role in Africa, it is tremendous. I was a child – I’m originally from Algeria – the first foreign doctor and the first medical team that was based in an overseas country was Algeria. It was in 1964 and up to today, there are these rotating medical teams. There are hundreds of thousands of Algerians whose babies were delivered by Chinese doctors and you also have traditional Chinese medicine and acupuncture and everything. That’s to clarify that China’s health diplomacy, if you want to put it directly it’s health diplomacy, but it has served the People’s Republic of China in using it as soft power successfully. As someone who travels to Africa, I’ve seen the number of hospitals that have been set up there, including dealing with those diseases and infectious diseases. During Ebola, the Chinese were already present in the field of helping.

This is all underpinned by a philosophical conception in Chinese soft power or health diplomacy which has been now connected to the Belt and Road initiative.This is why I say it’s not new and you look at the Belt and Road which has a parallel element which is the ‘Health Silk Road’ whereby China said that they would build hospitals along the road treating the sick and training people. The philosophical underpinning is this notion of South-South cooperation on development and this notion that some scholars call moral realism in the sense that you do it for the common good, including the vaccines. There was that pledge from the Chinese that as soon as they discover vaccines, they would try to give it or sell it at a low price to the developing countries and that the three pharmaceutical companies, SinoVac, Sinopharm and the other one whose name escapes me now, they have started and now there are many Middle Eastern countries that are going to manufacture the vaccine.

The way that China is advancing it’s, if you wanna call it, soft power, give it another name, but it’s the reality on the ground and that’s why I insist on this notion that it is not new now. Now that it has another dimension to reach some other objectives, it’s something else. The collaboration in the health sector that is so deficient in so many Middle East and North African countries. It was no surprise when the Chinese suffered the virus in the beginning, you had all the Middle East and the MENA countries contribute something to China. As soon as it happened in the MENA itself, I was in Doha at that time doing my fellowship, I saw Qatar Airways, which was one of the only airlines delivering the medicine. It was not just to Qatar but also to the rest of the region and they had those online discussions with the doctors exchanges. If you look at the narratives coming from the Middle Eastern governments, they have adopted the very same language that the Chinese would use. This notion of shared common destiny – this new narrative that the Chinese have come up with.

What was fascinating – I did the whole study on China’s health diplomacy under the pandemic. What was amazing is that China did not give only to this or to its partners in the beginning. I thought okay the aid would go to countries that are favourable to China or have been friends with China for a while. It was not the case and you could see the cooperation with Saudi Arabia, with the UAE, with Israel, and with Turkey. There was a little glitch with the Turks regarding Armenia because there were some packages which had the name in Armenian. It was resolved rather quickly, but what I’m saying is that this health diplomacy has been around for a long time and I believe that it will continue. It has resulted in, not just a positive image on the part of the government and Jonathan has explained how they looked at the governance or how they managed to contain the virus, but also at the popular level. In other words, if you look at the recent opinion polls in the region, most of them are rather positive and they are negative towards the Western powers.

By the way, I live in France and they haven’t been able to deliver to everybody yet, let alone give to the developing world. There are donations of this vaccine. Egypt is receiving a lot, some of which was coming through the UAE but now it’s donated directly. Algeria has gotten it. Morocco has also gotten it and is going to manufacture it to distribute it elsewhere. Overall they have done quite well and the populations in the MENA are not going to question whether it’s Chinese or Russian. It’s a necessity and they know that they’re getting and there are some advantages. Judy talked about Sputnik and even the conservation and when you think about the logistics and the cost – it is quite appealing to developing countries.

Dr. Alan Whiteside: Let me go to COVID more broadly and talk about that and then we can move on to the discussion. I think we need to be aware that COVID is affecting all our lives in ways that we had no idea it would. It is without doubt the biggest health crisis of my life. I came into health and health work via HIV and AIDS. Just so you’re all aware we’re talking about 125 million people infected at the moment and that number continues to rise. Most people don’t get seriously ill and the risks are age and underlying health conditions but COVID has stopped the world and it’s changed how we live. It’s changed how we work and it may even change our values and that’s a very important point to discuss with regard to diplomacy. The OECD is the hardest hit. The USA has over 30 million infections. Countries with over 10 million infections are Brazil and India. In Europe, you have Russia, the UK, France all over four million. Italy, Spain, Turkey, Germany, Colombia, Argentina, Mexico and Poland have between two and four million and so it goes. The rest of the region has fewer than half a million and the question which we would ask ourselves is ‘Could numbers rise?’ and the answer is in the absence of interventions, yes. Now let me just say for anyone who wants to go into this in more detail and look at individual countries, a really helpful website is the Johns Hopkins coronavirus website and you can actually fiddle with the numbers there and look at what’s going on in your area.

Why vaccines? Well the answer is that non-medical interventions or as we call them NMIs are very limited: masks, physical distancing (and I prefer physical to social distancing) and hand washing. That’s really about it. Everything that we do other than those are actually subsets of that so a lockdown is an enforced physical and social distancing. The idea of herd immunity, well it’s been argued but who knows, so we really do need a vaccine. This is going to be the way we get out of this and it’s going to be the way that we achieve the maximum return. I think it’s probably worth noting that the question of who gets the vaccine is quite an important one to have discussed. It needs to be discussed at a national level. If you want to achieve the maximum in saving lives or prolonging lives, then you want to give it to the most vulnerable people who are the older people. If you want to do the maximum for the economy then you want to give it to a different group of people and that’s a conversation which each country needs to have.

So what vaccines do we have? We’ve got three from the west: Pfizer-BioNTech which is the first to come out. It’s quite difficult to store and administer. Oxford University and Astrazeneca, and if we want to have a conversation about global health diplomacy, oh my word, there’s the place to be with the fight going on between Britain and the European Union at the moment. It’s so complicated. I was on a radio program this morning and they said to me, ‘Can you explain it?’ I had to say ‘No I can’t, you haven’t got long enough.’ My word, there’s an example for vaccine diplomacy going into the future. Of course we’ve got the Russian Sputnik which as Judy said is $20 and then we’ve got the three from China. Now the problem with the Chinese vaccines is we don’t know much about them and I think you probably do if you read Chinese but if you don’t you don’t know much about them. That leads to a Western view that if we don’t know much about them they’re probably not that good and I think that’s a really important point to be aware of so we need to make vaccines accessible.

COVAX is the international project which is to unite the world and ensure that people will have access to vaccines. I’m not certain where the Chinese vaccines fit into COVAX. It’s a lack of information which I have. The reality of where we are with vaccines is that with the exception of Israel, which is over 100%, the UK, the USA and countries like the UAE, Chile, Qatar and Bahrain, the world is doing really horrendously. I’m sure my colleague from France could make comments on how appallingly badly they’re rolling out their vaccine initiative there. Here [in the UK] we’re well over half the adult population and it’s going forward very very quickly.

What about ways forward? I’m going to say there are two possibilities. One is that in the best world everyone who needs protection gets it and we can talk about who are the people who need it. It may not be healthy 25 year olds, but people like me, yes, definitely, I’m afraid. I’ve had my first dose. The second and so the best situation is everyone gets protection and the pandemic is brought under control. We will need boosters. In the worst situation, we have variants which are more infectious and more deadly and we need adjusted annual vaccines or perhaps even more frequently.

Questions from Moderator

Moderator Jacopo Scita: Dr. Fulton I’ll start with you. So my first question is: Can you elaborate a little bit on how the COVID-19 pandemic had an impact on public opinion especially in the Gulf towards China? How has Beijing vaccine diplomacy, which has been on full display in the Persian Gulf, served China’s interest in the region? How has this impacted the public opinion in the Persian Gulf?

Dr. Fulton: Well it’s tough to measure public opinion because that just simply doesn’t exist in most of this region. You can find things like the Arab Barometer that looks at some countries in the Middle East but in the Gulf you’re not going to find very much reliable data. I live in the UAE where different Emirates are using different vaccines. In Abu Dhabi, they use the Sinopharm and they did the trial here. They’re doing a lot of cooperation with China on Sinopharm and you see leaders and civil servants and everybody’s had access to it. They very publicly use it.

It’s quite interesting because the younger generation grew up in a world where China was seen as a powerful country. I was born in 1975 so when I was growing up, China was still kind of seen as the place where they made cheap junk that nobody wanted but my students don’t see China this way. It was seen as the second rank of electronics or consumer goods. Now they’re like hey SinoPharm. China’s seen as a positive provider of public goods whereas before it was always kind of seen as a free rider in the Gulf just kind of piggybacking on the American security guarantee to just kind of build economic relations. That’s just not the case anymore. It’s gone from being seen as a follower to more of an active participant.

China’s been trying to change this narrative with the Belt and Road Initiative since 2013. It is a contributor to global public goods and a lot of folks in the West will roll their eyes but here in the region they don’t see it this way. They see China as playing a more positive role. In terms of how people see it on this side of the Gulf, it’s quite positive. On the other side of the Gulf in Iran that’s a different matter. There they have a much more vibrant press. You could see especially during early days of the pandemic when Iran was brutally hit, people were incredibly critical and they got to a point where I believe a spokesperson for the Ministry of Health had made public comments about how he didn’t believe the Chinese numbers on COVID and that very day somebody pulled in from the camera and said ‘Take that back.’ Here in the UAE they were the first place to publicly release the trial data on trial three of the Sinopharm.

It has changed public perception. It’s changed elite perceptions. China’s gone from being seen as a country that you can do business with but not really rely on for much else. That perception has changed tremendously here in the Gulf and I’d say throughout the rest of the region. This Abraham Accord, there’s a lot of coordination between China and the UAE and Israel and I know that’s seen as a diplomatic coup for the US but this is something where China’s actually made pretty substantial gains as well. Just before I came on, a lot of people were contacting me on Twitter. The Chinese foreign minister is here in the Gulf for a very big visit – six countries in the Middle East over the next week or so and he’s in Saudi Arabia today advocating for a Chinese-led mediation between Israel and Palestine. I don’t believe anybody in Israel or Palestine wants a Chinese answer to this question. It’s just a change of perception where people are seeing China as an important actor. It definitely has changed in how people see it here.

Moderator: The next question is about great power competition that is going on in the Middle East and we will see developing in the next few years. Do you think that the COVID-19 crisis and the subsequent vaccine diplomacy will somehow give an advantage to China in this supposed great power competition in the Middle East and specifically in the Gulf or vice versa? Will we see a negative impact on Chinese momentum in the region?

Dr. Fulton: This is an interesting one for me because it’s kind of hard to balance this question. You either sound like a ‘panda hugger’ or ‘panda slugger.’ I don’t think I’m either. I’m a political scientist so I try to keep a pretty neutral look but from what I can see this whole idea of great power competition is really something people in Washington DC talk about a lot. It’s not something people in the Gulf talk about a lot and it’s certainly not the way China looks at the region. Now I don’t mean China’s pure as the driven snow. China has interests and they pursued it in a certain way. If you look at the way China has approached the Middle East, this could take like an entire hour for me to go through but i’ll try to do it quickly, if you look at things like the Belt and Road Initiative White Paper or the China era policy paper, they’ve gone out of their way to develop a presence in the Middle East that actually compliments America’s leadership. They don’t see themselves as competing with America or challenging it. They don’t want to have a militarized presence. They want an economic driven presence. They’re here to make money basically, for good or for bad.

If you look at the countries except Iran that China does the most business with, that China is closest to, they’re all US allies and that’s by design. China is trying to develop a presence here that promotes the status quo because the Belt and Road Initiative needs stability. You’d see that countries like Iran or Qatar until recently that were kind of outside the status quo weren’t getting a lot of Chinese projects or contracts or investment, whereas a country like the UAE or Saudi Arabia or Egypt were getting boat loads of Chinese money in contracts so I kind of reject the premise of the question. I don’t think they see it in terms of great power competition. They see it in terms of opportunity and certainly COVID has provided a lot of opportunities for them but one of the things that we’ll see is China’s going to work very hard to try to develop a more positive relationship with the US because they’re not ready to challenge the US in any of this stuff. They don’t have power projection in the Gulf in the Middle East and I don’t think they have aspirations for it. Their core interests are domestic. Their core concerns are domestic pressures, economic pressures and governance Issues. I don’t think they see themselves in a position to challenge the US and anything really at this point.

Moderator: I will now move to Dr. Twigg and the Russian side of the equation. You talked about the three goals of Russia vaccine diplomacy in the Middle East. My question is, as a consequence of Russian vaccine diplomacy in the Middle East, will we see renewed Russian momentum in the region? What’s your forecast?

Dr. Twigg: As we look at American policy in the Middle East, we’ve got the Biden team very much still putting together its Middle East policy right now trying to recalibrate relations and move away from President Trump’s one-sided alliance with Saudi Arabia. Russia is taking advantage of this moment and this transition period trying to make it clear that its impact on the Middle East can be a match for the US. Russia is trying to position itself as a moderator and as an influencer, not just as a provider of arms but also as a provider of vaccines. If we remember early in the pandemic, a year ago, Russia’s relationships in the Middle East had taken a negative turn. Russia and the Gulf states and OPEC couldn’t agree on production quotas and that led to a pretty sudden drop in oil prices. That was a low point. Sputnik V has given Russia a new opportunity in the region. The Russian vaccine has been approved by more than a dozen Middle Eastern and North African countries. Some are aggressively using it. It’s in clinical trials in the UAE. Preparations are underway for transfer of technology to establish production of Sputnik V in Turkey and Egypt. There are talks about conducting clinical trials in Saudi Arabia. Tens of thousands of doses have been sent to the Palestinian authority, so Russia is pretty clearly trying to engineer a reputational shift here.

After having intervened militarily in the region, the donation of vaccines gives Russia a chance to present itself as more of a humanitarian actor. One more thing I’ll note here is that we’re starting to see examples of vaccines used in the region as diplomatic currency. Last month, Israel made a deal brokered by Russia to pay for a shipment of Sputnik V vaccines to Syria in exchange for the safe return from Syria of an Israeli woman who had been detained after illegally crossing the border. I won’t be surprised to see more of these kinds of transactional arrangements.

Moderator: You mentioned the US at the beginning of your answer. Russia and China have been much more proactive in this vaccine diplomacy than the US. Why has this happened?

Dr. Twigg: Early on, we saw the Trump administration in the US very explicitly pursuing an ‘America first’ approach. There was no attempt to hide it. They boasted about an ‘America first’ approach. That involved massive pre-purchase agreements of enough vaccine doses to vaccinate the American population many times over. That was an attempt to diversify the portfolio to make sure we had plenty of whatever vaccine would end up panning out from a scientific and regulatory perspective. Politically, that may have been a smart move within the US but of course that leaves, as has been the case with HIV, AIDS with H1N1, the rest of the world sitting on the sidelines for months or even years. The Biden administration has definitely tried to turn that situation on its head both in terms more broadly of American participation and global health institutions. We said no to the withdrawal from WHO and immediately joined COVAX, the global facility, to try to ensure vaccine access that Alan mentioned a few moments ago. Now we see the US agreeing that it will send some of its excess doses of the Astrazeneca vaccine, which has not been approved yet here, to Mexico and Canada and I suspect other places as time goes on. We clearly see a shift now in American policy the more we get into the Biden administration.

I think the key question goes back to some comments that have been made throughout this panel and that’s that when push comes to shove, will people in poor and middle-income countries really pay that much attention to where their vaccine has come from? As the rich world kind of catches up, especially the US and once Western Europe sorts out the mess that it’s in right now, in this vaccine diplomacy game, and as the narrative shifts more from one of vaccine nationalism to one of vaccine generosity and diplomacy, we hope equity, as time goes on, we will look back and say that China and Russia have kind of had their moment right now. Maybe that moment passes as we move forward and COVAX and bilateral deals involving Western countries that perhaps come on more favorable terms, better price points, better assistance with vaccine distribution, going the last mile to actually get vaccines into people’s arms. Do those arrangements end up sticking in people’s memories in the longer term?

Moderator: Let’s shift back to China, with Dr. Zoubir. China has used this COVID-19 pandemic to launch the ‘Health Silk Road’ which has been launched as part of the Belt and Road Initiative. Do you think that MENA and Africa have been receptive to this Health Silk Road? Once the pandemic is gone will the interests of the region towards China go back to this economic rationale that has so far dominated this encounter?

Dr. Zoubir: I don’t have a crystal ball. I don’t anticipate what will be but I can tell you from what I see today and how it will unfold. I focus more on the North Africa region all the way down to Africa itself. I tried to convey the point that health diplomacy is not new. It’s not going to go. It is part of this rationale or philosophical underpinning of diplomacy. It’s a big dimension. I remember when no one wanted to wear a shirt made in China. In Algeria, for instance, they said it’s made in Taiwan. They didn’t know the difference between the two but they would say that it’s Taiwan. Today there’s a different thing. They see the big projects, highways, buildings and housing. In my research on China in North Africa, you will see that some of the imports from China are not the cheap products. They consist of machinery and industrial goods and now you see the cars and what have you. There is a change of perspective so I believe that the economic relations will increase. They will continue, especially after COVID.

I follow the debates on who is going to recover first, who’s going to have a higher growth and so forth, but I think it will continue. The health diplomacy will still be there. The Chinese would still be pushing for this ambitious Belt and Road. As I said, the Health Silk Road is not just the Health Silk Road, it’s also the Digital Silk Road and so on. They’re all going together and they’re there to stay and the perception has changed. In the region they understand it and the more you push in that, culturally speaking, in that region that somehow the Chinese are bad, it does not work. The government will try to balance out each side. Diversification is helping them find new big players who can contribute to their development. At the end of the Trump administration, they were pushing ‘You’re with us or against us,; sort of the George W Bush mentality – that does not work. They’re going to use what they believe is in their own interest.

What I find sad from my perspective and maybe Judy because she follows Russia. I hope that the Biden administration, by responding positively at least in terms of promise, to give those two billion dollars to the World Health Organization is real and it’s not part of this rivalry but instead to work for the common good. I’m not being some sort of idealistic freak but it’s reality because for those of you who are familiar with health diplomacy and there was great cooperation between the US and China in Africa for instance and that worked. It worked even during Ebola so I believe that it should not be like “Aha since the Chinese are doing this I’m going to do that to compete with them.” Rather, how do we handle this? I join Alan on this one. We should not leave behind the ones who don’t have. There might be rivalry in the security sector or in some areas that’s normal among states, but there are areas which necessitate the cooperation of the great powers to help the developing countries. If not, we’re back to that – we are still in it – this widening gap between the poor. What is the point if we are all safe in the North and we’re safe and vaccinated but the rest of the world is not vaccinated and does not have access to medical care and doesn’t have access to the vaccine. If the Chinese are contributing, or if the Russians are really contributing to vaccination on a wider scale, why not?

I join Jonathan fully when he says he doesn’t see the Chinese being interested in supplanting the US or someone else in the region. They don’t give a hoots. The Chinese are there to do business. They want business and they want to work on projects. If it works, it works. If it doesn’t work, they pack and leave but they are there to build. Yes they have some geopolitical interests and they have interest in getting closer to Europe in some places to build ports, which is part of the Maritime Silk Road, but I don’t think they’re out there to want the US to leave. On the contrary, the US in the Gulf serves the interests of China. Their presence guarantees security. ‘Please stay, we’re not interested in getting into this fight between Saudi Arabia and Iran or in the region or the Western Sahara conflict.’ If they can stay away from those troubles, they would.

There are some areas where competition or sort of rivalry is positive if you’re showing me that you are providing serious development aid or industrialization, that’s good for everybody. I remember interviewing one of our ambassadors in Africa and I asked him ‘What do you think?’ It was under the Obama administration and he told me he said look – I won’t name the country to keep his anonymity – but he said it’s great that China is here because they’re building the infrastructure and this infrastructure is good for our business people. I think it could be that this kind of collaboration instead of rivalry is helpful to the rest of the continent or the rest of the developing world.

Moderator: Dr. Whiteside, one of the trends we have seen right now with this COVID diplomacy in the region and the referendum to the Middle East especially is that countries in the region are relying on great powers to develop and supply the vaccine and perhaps the only exception is Iran which is trying to develop its own vaccine. Do you think this will have some sort of impact on these countries’ health systems and medical research? What will we see coming out from this crisis and this over-reliance on great powers for health?

Dr. Whiteside: We need to recognize that, although science has become simpler in some ways, it still requires a great deal of investment so we’ve got centers of excellence. I think of the area around Cambridge in the UK or in parts of the US. I do think that you will tend to see the best developments coming from those centers of excellence whether they’re in the West or in China or in Russia. I don’t believe that most countries would be able to start and develop things from scratch. There’s a constraint of science, a constraint of laboratories, a constraint of a history, of doing biomedical research so I don’t think it would be good use of resources to start trying to set up something completely new, but you can partner and I think that’s what we’ll see more and more of.

Moderator: Do you see vaccine diplomacy in the Middle East as more of a political concept or a medical concept?

Dr. Whiteside: I think that is very interesting. One of the reasons why it’s so interesting is because I think there are questions about where diseases will come from. We did see the rise of MERS which was the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome in the Middle East. I think the answer will be, if you talk to the medical people, it will be medical diplomacy monitoring and looking at what’s going on. However, I don’t know how much will come from the Middle East because it’s not where most zoonotic transference of diseases will happen. That will be in highly dense populated places or subtropical places.

Dr. Zoubir: It has been politicized. It has been put in this sort of rivalry which I’m condemning because from the very beginning, if you compare the MENA region with Europe or the US, in the MENA, there was a very positive reaction to it. In the West, it was mask diplomacy. Most of the articles were ‘Aha you see what the Chinese are doing.” Again, I am not a Chinese lover or basher. I try to be objective but it’s been politicized and that wasn’t healthy.

The problem too is that the Chinese also made some mistakes. Some diplomats bragged about the success, but I think they learned the lesson. I see that today we are pushing for further politicization. The fact that if you follow what’s going on in Europe, Merkel had said that she was welcoming Sputnik V. All of a sudden now the Europeans are mostly negative. One needs to separate what is something for humanity and what is core interest. The fact that, if the Russian vaccine is good and it’s proven to be 92 percent effective, let it come to the people. Here, they told us they started going with the Astrazeneca vaccine. Then, they suspended it. Now, they may start it again and then the US is now saying, wait a second Astrazeneca, maybe the data was not all that correct. It’s scientific, it’s medical. If not, you’re encouraging those who say ‘Oh I am not going to get vaccinated’ and here we have a big percentage, especially now after the suspension, although it has resumed, of people who question whether it was necessary to vaccinate or not. I think this politicization of something that is so important to humanity as a community is wrong.

Moderator: Another quick question is, do you think the COVAX program is successful, and will be successful in, giving and spreading vaccines, especially in those countries that have had more difficulties to get access to vaccines? If not, is there something else that great powers can do in that realm?

Dr. Twigg: As recently as a couple of months ago, we all thought COVAX was on life support. It looked like it might never have gotten off the ground. The acceleration of COVAX is remarkable with the commitments from the Biden administration and others very recently. I’ll just note that earlier this week, Russia indicated that it had applied to have Sputnik V included in the COVAX portfolio of vaccines. That’s a vote of Russian confidence in where COVAX is going to sit in terms of provision of vaccines to the world.