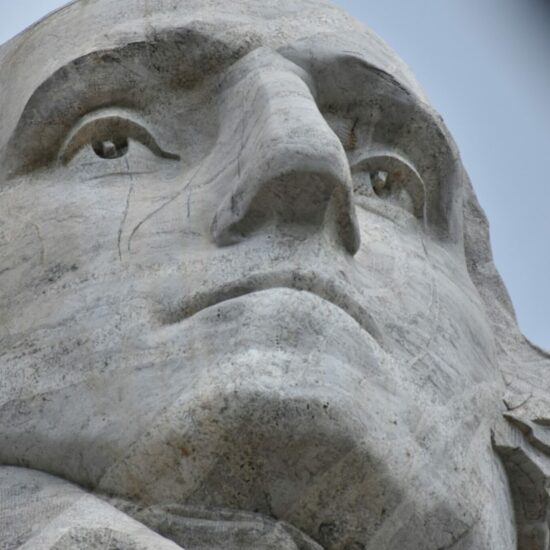

“Swimming is prohibited, danger of drowning”: written on the billboard near Hajiabad Dam located at South of Khuzestan Province bordered with Iraq. Source: Mojtaba Gorgi, Feb 2017, IRNA.

By Barney Bartlett, Karen MaKuch

Abstract

US foreign policy has long failed the environment along the Iran-Iraq border. American efforts to stabilize Iraq have countered its actions across the border in neighbouring Iran, which has centred around the use of coercive measures for decades. This polarization in US foreign policy has overlooked the environmental inextricability of the resource abundant Iran-Iraq border, inadvertently contributing to instability in the region.

Whilst Iran and Iraq are home to unique historic and cultural contexts, the social, economic, and environmental realities of these neighbouring states are much the same. Both countries are facing ongoing issues with water scarcity, the mismanagement of local resources, climate change and increased political dissent amongst locals. Due to the inseparability of Iran and Iraq’s environmental security, the environmental ramifications of stringent US sanctions against Iran are spilling into and exacerbating existing challenges in Iraq.

The Biden administration now has an unprecedented opportunity to place climate policy at the forefront of American policymaking, both at home and abroad. This will necessitate a serious re-evaluation of US soft and hard policy tools that inadvertently undermine sustainable development. This is exemplified in this work through the examination of economic sanctions and their inadvertent environmental impacts, using Iran as an example.

Results discuss how US sanctions policy has long overlooked environmental concerns. Recommendations are intended to guide future US foreign policymakers on methods to mitigate the potentially deleterious impacts of sanctions in a target state, minimize confrontations and promote sustainable development on an international level.

Introduction

Amongst the many tasks of the incoming Biden administration will be moving the United States towards an ambitious new climate agenda, a feat that will require a radical transformation of thinking and practices across all areas of American policymaking. To actualize global leadership in climate policy, it is integral that this transformation is not limited to domestic affairs, but that environmentally conscious policy decisions are integrated into how the US acts abroad through its foreign policy agenda. To do so will require not just engagement in diplomacy with a climate focus, but a total re-evaluation of America’s hard and soft foreign policy tools, namely economic sanctions.

In the post-Cold War era, economic sanctions emerged as the US foreign policy instrument of choice, often viewed as an effective alternative to conventional war. However, the impacts of these restrictive measures on the population of a target state have been compared to that of war, including but not restricted to, increased levels of poverty and significant declines in the GDP per capita of the target state. In recent years, this foreign policy tool has been met with increasing criticism for its unintended humanitarian impacts on target nations.

The unintended impacts of sanctions on the environment of a target state are clearly visible in the case of Iran, a nation that has been subject to incessant economic pressure – mainly by the US for over four decades. Today, Iran is struggling to manage domestic social and economic distress, partly provoked by the ramifications of prolonged sanctions on the state and battling an ever-worsening environmental crisis. Moreover, the early onset of the Covid-19 virus in Iran has strained its already fragile economy to a breaking point.

Iranian policymakers have increasingly acknowledged the understudied association between economic sanctions and environmental decline, citing sanctions as an impediment to Iran’s pursuit of sustainable development and the safeguarding of its natural environment. Despite a growing awareness of the unintended humanitarian impacts of sanctions on targeted nations, US policymakers have consistently overlooked the secondary environmental consequences of this coercive tool in sanctioned states, demonstrating a serious failure in US sanctions policy.

President-elect Biden has promised to redesign US policy on Iran, in particular, the punitive use of unilateral sanctions employed under Trump’s presidency. In doing so, the incoming administration has a unique opportunity to set a crucial precedent of placing global climate strategy at the forefront of American foreign policy. Biden’s recent appointment of former Secretary of State John Kerry as climate envoy, a newly established role, already illustrates the importance of climate change to this new administration. Kerry, who served as the chief architect of the Iran Nuclear Deal and signed the Paris Climate Accord on behalf of the US, may inspire the integration of climate diplomacy on multiple fronts in future US policymaking.

Source: Secretary Kerry Introduces Vice President Biden at the 2016 Chief of Missions Conference

Following the implementation of the Iran Nuclear Deal or Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) under President Obama in 2016, it was anticipated that sanctions relief would allow Iran to engage in a much-needed exchange of knowledge, capital and technology. This would ultimately be to the benefit of the country’s environment, which has suffered from outdated and inefficient industrial and agricultural practices. But under the Trump administration, such prospects became more and more illusory, culminating with the United States unilaterally withdrawing from the JCPOA and embarking on the “Maximum Pressure” campaign against Iran in 2018.

Ever since, Tehran has been subjected to arguably the most testing economic sanctions since the 1979 Islamic Revolution, manifesting in severe economic, social and environmental tolls on the country, seemingly without prompting a desired change of behaviour from Tehran. Although the Trump administration has consistently claimed its “Maximum Pressure” campaign was “targeted at the regime, and not the people of Iran”, the reinstatement of sanctions under this administration targeted critical sectors of the country’s economy, such as the energy, shipping, automotive, aviation and financial sectors, which are all crucial to sustainable development. In fact, the ramifications of sanctions on Iran have even extended as far as impeding Iran’s ability to receive grants for environmental efforts from international funding institutions, such as the Global Environmental Facility (GEF), a subsidiary of the World Bank. Furthermore, sanctions have hindered Iran’s ability to acquire essential dual-use items, like relief choppers for disaster risk management.

Iran and Iraq’s Environmental Security: Bound Together by Fate

Though much of the blame for Iran’s current environmental predicament must be attributed to endemic oversight and issues of mismanagement on the part of Iranian policymakers, it is undeniable that sanctions against the Islamic Republic have had damaging secondary consequences on the local environment, which has endangered not just Iran, but also neighbouring countries, namely Iraq.

Despite the interconnectedness of the environment of the two nations, Iraq has been subject to a completely polarized form of US foreign policy from that of Iran. Since 2003, Washington has channelled billions of dollars into Iraq – providing $345 million in humanitarian aid alone in 2020 – to promote recovery and pursue economic and political stability.

From a policy perspective, US objectives in Iraq are heavily contingent on its aims concerning Iran. Whilst the US is working to stabilize Iraq, its presence in the country also provides it with key leverage in negotiating with Iran. This is why disputes between the US and Iran escalate endemic tensions in Iraq, recurrently aggravating existing discord between Iraq’s fragmented political factions and leaders. The prioritization of US policy goals in Iran over Iraq has “resulted in a zero-sum game”, where the advancement of security and economy of both Iran and Iraq have become inextricable. Thus, as US sanctions on Iran continue to indirectly provoke environmental insecurity locally, the ecological and national security of Iraq could be equally compromised.

The land straddling the Iran-Iraq border is abundant in natural resource wealth. The area has been long prized for its vast oil and gas reserves, as well as home to the most fertile and valuable agricultural lands in both countries. In recent decades, local resources have been plundered by both nations with little regard for the environment – most notably the ecologically and biodiverse Mesopotamian Marshes, a recognized UNESCO World Heritage Site and an important ecoregion fragmented across both nations. As a result, this formerly revered “cradle of civilization” is now increasingly desolate and parched.

On the Iranian side of the border lies the industrial province of Khuzestan, which has suffered badly from the country’s environmental troubles. Since the 1970s, an aggressive history of dam building married with a programme of river water transfers has significantly decreased river flows and the province’s formerly expansive fertile marshes and cultivable land are drying up. Heavy winds carry dust particles from these drying waterbeds that coalesce with emissions from heavy industrial activity in the province, creating some of the most polluted air in the world.1 The growing spectre of food, water and clean air insecurity is escalating tensions in a province that has historically chafed with Tehran, and in recent years, Khuzestan’s provincial capital of Ahvaz has witnessed protests of increasing regularity and severity.

Across the border in Iraq, a very similar situation is at play, whereby the quality and quantity of water entering the country has been drastically impacted by Iranian activities upstream. Falling river flows are drying up the country’s fertile marshes and cultivable regions in the south-east. Vast areas of previously fertile land are fast becoming arid, increasing rural poverty, which has collectively created a suitable recruiting ground for extremist groups. As rural opportunities decline, many are migrating to over-populated cities, increasing tensions and placing pressure on the country’s already failing urban infrastructure. In the south-eastern city of Basra, water shortages and contaminated drinking water have created undue strains on the country’s crumbling healthcare system, triggering widespread violent protests in 2018.

Decades of US sanctions against Iran, the legacy of the Iran-Iraq war between 1980 and 1988, and ongoing conflicts in Iraq have hampered the ability of each nation to effectively address its respective environmental challenges, most prominently water scarcity. These factors, when compounded with transformations in local demographics, recurrent droughts, the mismanagement of regional resources, and the effects of climate change, have collectively left unforgiving impacts on the local environment.

Iranian policymakers are largely to blame for the reckless pursuit of accelerated national development under such strict economic constraints. Nonetheless, it must be acknowledged that Iran had diminished autonomy in its decision making under the plight of coercive and restrictive sanctions. Prolonged economic sanctions on Iran limited the nation’s access to resources, compelling it to pursue a programme of self-sufficiency. In an attempt to pursue rapid industrial and agricultural development, Iranian policymakers overextended the nation’s finite domestic water resources, critically destabilizing the environment.

Meeting of Senior officials of the Environmental Protection Organization headed by Iranian Vice-President Eshagh Jahangiri (right) and Isa Kalantari (left), Iran’s Head of Department of Environment. Source: Office of Vice-President of Islamic Republic of Iran.

Though the environmental security of Iran might not strike American policymakers as of utmost importance, attention must be given to the fact that the inadvertent impacts of Iran’s environmental struggles range well beyond the nation’s national boundaries and have potentially grave implications for local and international security. This is especially important, as climate change is emerging in the policy realm as a security ‘threat multiplier’ – especially in developing states and conflict zones.

In recent years, it has become more apparent in both academic and policy communities that global linkages, socio-political change, human mobility, urbanization and climate change are interrelated realities that can no longer be viewed in silos. Namely, extreme climate events, such as droughts and floods, have the potential to significantly impact water resource management, agricultural yields, and critical infrastructure in vulnerable regions of the world, which can contribute to significant difficulties for communities living in such contexts. Whilst there is no direct causal link between environmental damage and economic sanctions, in the case of Iran, sanctions can be similarly viewed as a “catalyst” in promoting environmental degradation with local, regional and global implications.

Accordingly, US efforts in Iran and Iraq appear to have been largely counterproductive upon examination of the myriad of environmental, social and political issues along the Iran-Iraq border. The pursuit of short-term power and political gains have superseded intermediate and long-term interests in sustaining some of the region’s most important ecological resources. Seeing as the environment is now increasingly viewed as a matter of shared responsibility on an international level, the US cannot continue to overlook the environmental footprint of its foreign policy.

Though man-made borders divide the shared natural resources of Iran and Iraq, it goes without saying that the fate of the environmental securities of both nations is inseparable. The significant human and financial costs made by the US and its allies to stabilize the socio-political situation in Iraq are being carelessly undermined by American sanctions in neighbouring Iran, which has contributed to environmental strife now affecting both nations.

A Roadmap for a More Sustainable and Secure Tomorrow

Moving forward, it is imperative that environmental considerations be placed at the forefront of US foreign policy to mitigate their unintended repercussions. When dealing with Iran, US policymakers must place heightened consideration on understanding the potential humanitarian and environmental costs of sanctions before implementing a new policy agenda. In the same vein, Iranian policymakers should be more cognizant of their decision-making under sanctions and seek to minimize the environmental costs of their actions, instead of lauding and prioritizing an economic path of resistance, which has come at the cost of irreparable natural resource strain.

Further, financial mechanisms similar to the Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) for humanitarian trade with Iran called “Instrument in Support of Trade Exchanges (INSTEX)” and special waivers issued by the US Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) should be explored on environmental grounds. In doing so, legal pathways for the crucial exchange of clean technologies and know-how with sanctioned states can be established, to assist promote sustainable development in a targeted nation, even in light of stringent economic and political constraints.

Heightened US pressure under the Trump administration did not contribute to an amelioration of the key economic, environmental and security concerns of both Iran and Iraq. Therefore, the Biden administration should cautiously explore a different form of engagement with Iran, though gaining Iran’s trust after the US abandonment of the JCPOA will be arduous. Nonetheless, small and gradual sanctions concessions can play a monumental role in providing Iran with some desperately needed capital. If this sanctions relief is channeled appropriately into social venues and in combating coronavirus locally, this decision has the potential to both improve living conditions for the Iranian public and ease tensions along the Iran-Iraq border.

In this forthcoming transitional period in US administrations, there is a key opportunity to address this overlooked failure in sanctions policy, which has created immense obstacles in bettering the environment of target states for far too long. By moving towards a more environmentally focussed foreign policy model when engaging Iran, the Biden presidency has the potential to contribute to, rather than erode further, the environmental security of Iran, Iraq, the Middle East, and the wider world.

1 Ahwaz, Khuzestan’s capital city, earned the title as the most polluted city in the world in 2013 in the World Health Organization rankings.

Barney Bartlett holds a MA in South Asia and Global Security from King’s College London’s Department of War Studies where his research explored conflict and the environment.

Karen MaKuch is a Senior Lecturer at Imperial College London’s Centre for Environmental Policy specialising in environmental law and policy and international law.