By Mahdokht Zakeri

If regional tensions are softened by the security threat of COVID-19, there could be space for more comprehensive peaceful negotiations in the future.

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused widespread disruption of human security across the world. As governments seek to overcome extraordinary public health and socioeconomic challenges, violent extremist groups are exploiting the crisis to their advantage in the Middle East. The chaos caused by the outbreak has created further space for terrorist organizations to bolster their presence and promote their activities in the region. Undoubtedly, it is much easier for these groups to operate in unstable environments, where states struggle with underlying vulnerabilities in critical infrastructures such as health care and security services.

Amid this atmosphere of uncertainty, hostile organizations like the Islamic State (ISIS) have been revitalized by such an unprecedented opportunity to reinforce their narratives and capitalize on fear. As a result, ISIS has coordinated more assaults in areas where state governments are failing to establish an effective security presence. Recent terrorist attacks in Iraq, Syria, and Yemen demonstrate the severity of such threats to regional security in the Middle East.

The closure of universities and schools, rapid transition to remote working, and growing rate of unemployment have forced people to spend much more of their time in isolation, and online. This has provided fertile ground for extremists to engage with wider audiences via social media and chat forums. Here, they target vulnerable individuals with discourses and propaganda, intending to radicalize and recruit them into their organizations.

With such potential to wreak havoc in fragile states and conflict-ridden areas, the pandemic must be considered as one of the most significant threats to achieving stability in the region. On one hand, COVID-19 has disrupted humanitarian aid flows, hindered peace operations, and indefinitely postponed ongoing diplomatic efforts. On the other hand, the weakening of states’ security forces has created the perfect conditions for terrorists to expand their operations. Evidence of this is already emerging: in July, ISIS and Al-Qaeda collectively killed over 70 citizens and military personnel in Syria. Despite ISIS’ reduced presence in Iraq, sporadic attacks in Diyala, Kirkuk and Salah al-Din provinces continued into June, killing 40 civilians and army forces.

While such organizations view the pandemic as an opportunity to increase their military strength, they have also attempted to provide health services to the communities they operate within to gain popularity. In Syria, the Hayat Tahrir al-Sham has taken advantage of the state’s neglect of the social welfare sector by strategically providing support services to citizens in controlled territories, thus locally delegitimizing the government’s authority.

A concerted and collective effort is needed to counter these emerging security threats in the Middle East. Neighbouring countries in the region have struggled to sustain effective cooperation, but a common threat like COVID-19 may incentivize a limited regional alliance. This shared crisis might serve as a foundation upon which countries could shift towards regionalism, engage in negotiations, and coordinate their responses to COVID-19—despite ongoing rivalries on other matters.

Moving forward, Middle Eastern countries should first establish a platform for dialogue where all countries could meet to collaborate on matters of public health, first and foremost being the COVID-19 pandemic, but also future sustainable healthcare infrastructure projects. Second, to address the challenges of radicalization and recruitment posed by extremists, regional information-sharing on cybersecurity should be enhanced to monitor the activities of hostile organizations and build legislative and technical capacity for intervention.

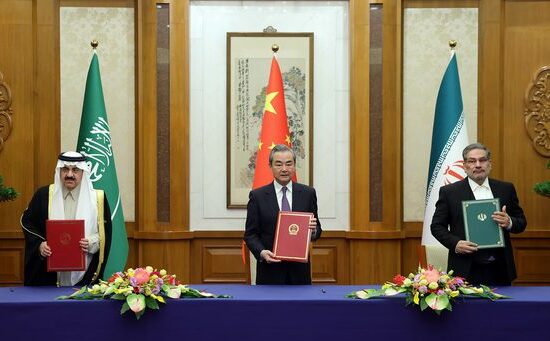

The Secretary-General of the United Nations, Antonio Guterres has repeatedly called for an immediate ceasefire in conflict regions. To stop the vicious cycle of instability, conflict, terror, and pandemic in countries like Yemen, Syria, and Iraq, a security consensus is needed in the Middle East. For instance, Iran, as a regional power, hard-hit by the pandemic, has an opportunity to call for cooperation with its neighbours and perhaps even reach some form of short-term agreements with rivals on ongoing regional conflicts. In recent months, some Gulf Cooperation Council members have demonstrated a willingness to engage in ‘virus diplomacy’ by offering humanitarian aid to neighbouring countries such as Iran, indicating a major shift in their foreign policy outlook. Thus, it could be the right time for Iran to initiate negotiations for achieving peace in conflict areas such as Syria and Yemen. In addition to improving regional security, preventing further escalation of ongoing conflicts, and reducing the spread of COVID-19, such measures could also provide the ground for negotiations on other vital long-term regional issues.

These diplomatic shifts and signals for constructive engagement can ripple outward. If regional tensions are softened by the security threat of COVID-19, there could be space for more comprehensive peaceful negotiations in the future. By showing a willingness to confront the pandemic through a multi-state platform, there might be a possibility for major regional players to re-engage and negotiate on ongoing regional conflicts, their relations, and a new order for the Middle East.

Dr. Mahdokht Zakeri is a visiting research fellow at the Center for Middle East Strategic Studies (CMESS) in Tehran. Researching at the intersection of identity conflicts and recognition politics, her interests lie in the study of violence and extremism, entanglement of misrecognition and organized crimes, and Middle East politics.

She has authored two books in Farsi, including Modern Barbarism: A Reflection on the Present and the Future of ISIS (2016) and Narcoterrorism: A Common Threat Against Human and National Security in the Middle East (2019). Her articles have been published in well-ranked journals in Farsi and English.

Note: The views and opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Institute for Peace & Diplomacy or its executive team.