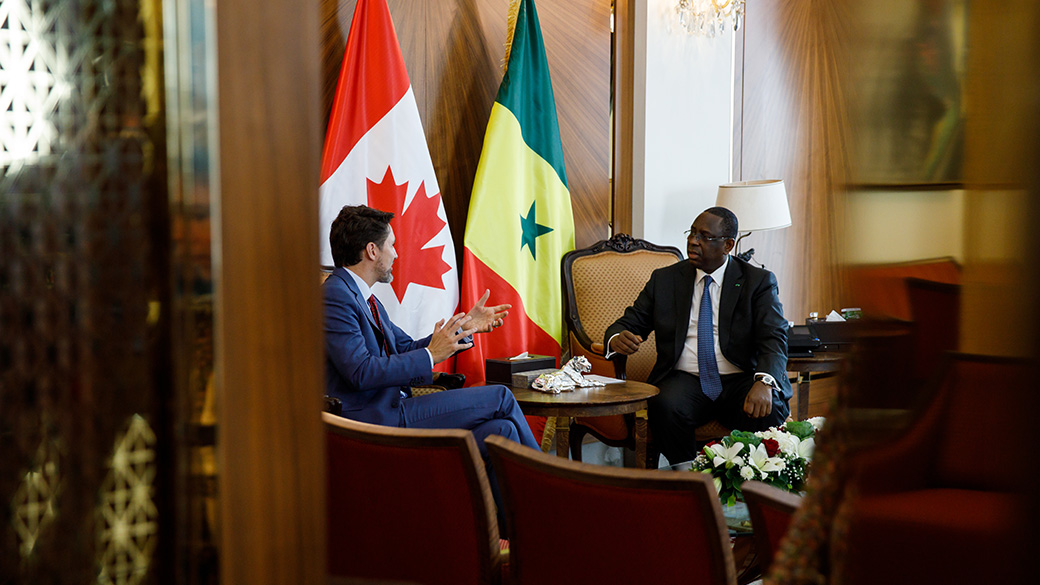

Prime Minister Justin Treadue meeting with President Macky SALL as part of his trip to Africa. Credit: PMO/ Feb12,2020

In the quest to gain a seat at the UN Security Council, the revival of peacekeeping missions is the most strategically prudent and the least costly alternative.

This article was originally published on The Hill Times.

By Pouyan Kimiayjan

Last month, Prime Minister Trudeau spoke to an audience of African diplomats in Ottawa and highlighted the importance of bilateral ties between Canada and African states. The goal was to garner their support for Canada’s campaign in securing a seat at the UN Security Council. With the vote coming up this June, Canada will need at least 128 votes that include 54 African countries. In doing so, the Prime Minister aimed to fulfill his “Canada is back” pledge back in 2015. However, while this direct appeal was meant to demonstrate the revival of Canada’s “middle power” doctrine, the Prime Minister’s speech fell short of promising renewed commitment to peacekeeping missions across the continent. In fact, following the recent conclusion of Canada’s deployment in Mali, the country’s peacekeeping contribution returned to historic lows. Currently, according to UN figures, Canada only contributes 45 troops to UN peacekeeping missions around the globe. In comparison, Ethiopia tops the list with 6639 troop contributions. These numbers reflect the staggering decline in Canada’s middle power status, particularly in Africa.

Since the Second World War, Canada’s embrace of the “Middle Power ” doctrine compelled it to increase its diplomatic presence in international institutions. This effort was followed by expansive peacekeeping missions. During the 1956 Suez Crisis, Foreign Minister Lester B. Pearson introduced the UN Emergency Force (UNEF), the organization’s first interposing peacekeeping force. This accomplishment, which contributed to the peaceful withdrawal of British, French, and Israeli forces from Egypt, won him the Nobel Peace Prize in 1957. Since then, with the sharp rise of Canadian peacekeeping contributions, peacekeeping had gradually become a symbol of Canadian national identity. The ten-dollar bill even featured a female UN peacekeeping soldier, under the bilingual writing “Au Service de la Paix / In the Service of Peace.” During the cold war, Canada ranked first as the dominating peacekeeping contributor and provided 80,000 troops (10% of all UN troops) before 1988.

Canada’s peacekeeping operations continued during the post cold war era. In point of fact, Canada’s peacekeeping missions increased significantly during this period. The 1990s had ushered in a new era, known as the second generation of peacekeeping. During this period, there was an unprecedented level of cooperation with the Security Council. The collapse of the Soviet Union had created power vacuums and civil wars across many former soviet-bloc states. Consequently, this environment compelled the UN to send an international peacekeeping force to the Balkans, where Canadians contributed a large part of the UN-led mission force and engaged in heavy combat with Croatian Forces.

Canadians were also greatly involved in UN-led missions in Rwanda and Somalia, being at the center of several scandals and controversies. Along with the significant decrease in Canadian military expenditure and the increase in US-led interventions, particularly in Afghanistan, Canada began limiting its contribution to UN peacekeeping missions. Canada’s close relationship with the United States ensured its security, in spite of the decline of its moderating presence in world affairs.

However, the emerging global shift in power poses a significant threat to Canada’s security and prosperity. The decline of US global power and the rise of China can be identified as the main factors driving this shift. Amid the current period of transition, Canada’s economic diversification and future relationships with other emerging middle powers, such as the BRICS states, will become significantly important. As a middle power itself, Canada needs to effectively compete for influence. These BRICS states are currently contributing a significant number of troops to UN peacekeeping missions, including 249 Brazilians, 78 Russians, 5404 Indians, 2544 Chinese troops, and 1151 South Africans.

Moreover, with the Trump administration’s increased hostility towards its European allies, Canada must in parallel intervene and help to preserve the trans-Atlantic alliance. This also means more troop commitments in regional peacekeeping missions. In Cyprus for example, beginning in 1964, Canada contributed 25,000 peacekeeping troops over the decades. While the number of Canadian troops dramatically decreased after 1993, a small group of Canadian peacekeepers remains there amid continued UN peace efforts. Today, with the rise of Turkish regional adventurism, Canada can once again emerge as the peace-broker in this region, increase its peacekeeping troops, and deter a potential conflict between Cyprus and Turkey.

Most importantly, while these missions help strengthen Canadian credibility abroad, peacekeeping missions have been less costly compared to US-led campaigns. With 125,000 peacekeeper deployments since 1948, Canada lost 130 of these troops, compared to the 158 death toll during its intervention in Afghanistan. In light of this, it is no surprise that such missions have repeatedly been endorsed by the electorate vis-à-vis the past two federal elections. Henceforth, in the quest to gain a seat at the UN Security Council, the revival of peacekeeping missions is the most strategically prudent and the least costly alternative. Canada has an opportunity to translate rhetoric into action prior to this upcoming June.