By José Niño

As emerging great powers like China and Russia have laid stake to their claims in their respective geopolitical backyards, the ‘sphere of influence’ (SOI) politics of yore has made a roaring comeback. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, liberal internationalists have insisted that spheres of influence are a thing of the past and that universal hegemony of liberalism would be forever permanent and irreversible. The specter of great power competition and the rise of the multipolar world order have already proven the folly of that claim.

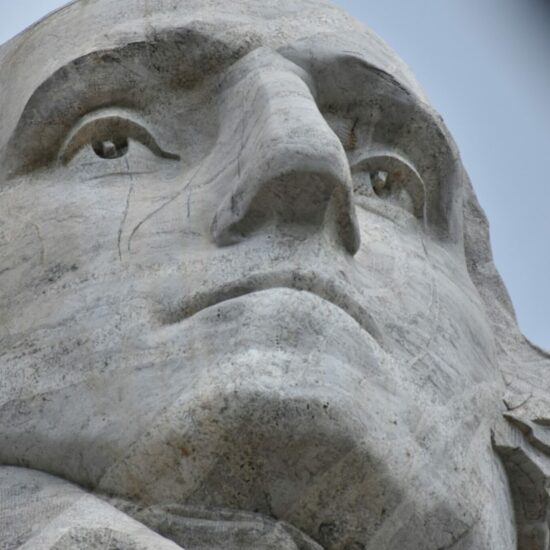

In 2013, then-Secretary of State John Kerry boldly proclaimed that “The era of the Monroe Doctrine is over.” The Monroe Doctrine was a pillar of American foreign policy throughout the 19th century: it declared the United States’ intention to turn the Western Hemisphere into a protected space for itself, effectively closing it off to future colonization and intervention by external powers. Following the conclusion of successful independence movements against the Spanish Empire, President James Monroe issued this proclamation in 1823 to defend American interests within the Western Hemisphere and keep European powers from re-establishing a colonial presence in the area.

By the end of the Cold War and the euphoric end of history moment it unleashed nearly two centuries later, however, the principal grand strategy that had guided American geopolitics for decades and permitted its rise into a great power had appeared all but discarded. And yet, history and contingency being alive and well, the Trump administration found itself having no choice but to make an about-face with regards to the Monroe Doctrine. Its framework was invoked when Venezuela was ensnared in a constitutional crisis — where President of the National Assembly Juan Guaidó found himself at loggerheads with incumbent president Nicolás Maduro over who should be the legitimate ruler of Venezuela.

Following the Venezuelan situation with interest, U.S policy makers immediately took issue with how U.S. competitors like China and Russia backed the embattled Maduro regime. Even middle powers like Iran and Turkey lent out support to Maduro, the latter helping Caracas skirt sanctions through its purchases of Venezuelan gold. As such, despite the Obama administration’s earlier repudiations, the Trump administration openly appealed to the Monroe Doctrine when it perceived that Venezuela could potentially offer the major challengers to the U.S.-led alliance a foothold in the Americas—proving yet again that geopolitics is the realm of necessity and realism, not idealism.

To be sure, the Monroe Doctrine and Manifest Destiny were products of their time, encapsulating the rising tide of continentalism in America. With the Louisiana Purchase and America’s conflict with Great Britain in the War of 1812 concluded, U.S. statesmen were leery about the fledgling Republic’s security and possible threats great powers of the period, such as Great Britain, France, and Spain, could pose to U.S. security designs by perpetuating themselves throughout the Western hemisphere.

Of course, the Monroe Doctrine also laid the groundwork for the creation of a de facto sphere of influence for the U.S. to exploit in the Western Hemisphere. Nevertheless, as political commentators like former U.S. presidential candidate Pat Buchanan have observed, the Monroe Doctrine also promoted restraint and non-intervention as a general principle. Although the Monroe Doctrine did outline the American ambition to keep European powers from re-colonizing the Western Hemisphere, the U.S. would reciprocate by not intervening in the internal affairs of European countries. Furthermore, the statement also affirmed regionalism, signaling that the U.S. would limit its own international reach and not interfere in the affairs of Asia and other distant regions.

U.S. grand strategy since the turn of the last century with the Roosevelt Corollary of 1904, and certainly since WWII, represents a radical departure from its rather defensive and territorialist 19th century origins, with Washington taking a more activist, expansionist, and imperial role in the context of Progressive Era politics. The Cold War only exacerbated and globalized the imperialist interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine. Today, in an age when the U.S. acts as a global hegemon touting the liberal international order and declares it its “duty” to intervene wherever it pleases to uphold Western values, U.S. policymakers’ cries for other great powers to respect the Monroe Doctrine and U.S. sphere of influence ring hollow.

Convinced that it is on a holy crusade to spread democracy abroad, the U.S. has not only shunned realism but has also acted in complete disregard to the national interests of emerging powers. The unipolar moment of the 1990s blinded many U.S. leaders and deluded them into thinking that the entire world could be poked and prodded into embracing liberal democracy. At the height of its hubris, the U.S. would use force to remake countries in its own image as in Iraq or even attempt to nation-build from the ground up as shown by the debacle in Afghanistan.

Despite the troubling course U.S. foreign policy establishment adopted since the end of the Cold War, the reality of multipolarity and the specter of great power politics are re-shaping international relations. Revitalized powers like Russia and China have accumulated enough mobilizable wealth to build military forces and economic levers that can stave off incursions from external actors in their respective neighborhoods. Naturally, when countries reach great power status, they move to protect their own red lines and interests within those geographical areas historically under their cultural, economic, political, or geopolitical domain.

Russia’s rise to challenge liberal hegemony has demonstrated how liberal internationalism is no longer uncontested. The mirage of unipolarity first dissipated when Russia forcibly asserted its interests in Georgia (2008) and Ukraine (2014), two countries Washington made an earnest effort to bring into NATO’s security architecture. Washington’s dreams of further expanding NATO on Russia’s borders came to a grinding halt when Russia used military force in South Ossetia and Crimea, thereby putting an end to the Atlantic powers’ post-1990 monopoly on the use of force in international politics.

Russian annexation of Crimea gave then-President Barack Obama a harsh dose of realism. Obama even conceded that Moscow held “escalatory dominance” with regards to Crimea in its disputes with Ukraine and the West. Despite the succeeding Trump administration’s decision to provide lethal military aid to Ukraine, most astute observers now concede that there was not much the U.S. could do in this conflict, lest it want to run the risk of stumbling into a thermonuclear war. Geopolitical realities have dawned on the Biden administration as well, whose tough talk on the campaign trail notwithstanding, has seemingly pursued a detente with Russia to focus more of Washington’s resources in efforts to contain China.

All in all, Washington’s desire for other world powers to respect the Monroe Doctrine shows that even with decades of liberal internationalism permeating foreign policy decision-making in Washington, America’s history of engaging in classical geopolitics continues to influence its conduct of foreign affairs. It is also not of marginal importance that the decision of America’s strategic rivals to encroach on U.S.’ geopolitical space is at least in part a reaction to what they see as Washington’s overreach across the globe into their respective regions.

At this juncture, the most effective way for the U.S. to prevent foreign intervention and expansion in the Western Hemisphere is by reverting to the realist basis and restrained principles undergirding classical American statecraft—with Washington clearly defining its red lines in the Americas. Furthermore, such demarcation of what it deems protected spaces will require the U.S. to also acknowledge that Great Powers like Russia and China, and even regional powers from Iran to Turkey all have similarly vital interests and historical influence within their own core geographic regions. Such an approach will surely seem provocative in Washington, but sober international statecraft must prioritize necessity and realism over fantasy and utopianism.

A full acknowledgement of the shifting geopolitical paradigm and the disposal of outdated and quixotic foreign policy assumptions are pivotal steps toward safeguarding American power for future generations and to return even a semblance of restraint to American foreign policy.

José Niño holds a Master’s Degree in International Relations from Universidad de Chile and a B.A. in Government and History from the University of Texas at Austin.